WORDS AND SILENCES (2022)

“Reflective, vulnerable, melancholic and hypnotic, this is a record for times of solace, companionship and escape. 5/5 stars. #2 Underground Album of 2022.”

“I found myself not just compelled but consoled by this music... Harnetty is to be commended for writing such gorgeous music, and for realizing such a project.”

“Harnetty, by harnessing the beauty of the grainy recordings, has given new life to these previously little-known words of Merton. By integrating his own musical orchestrations into Merton’s recordings, Harnetty provides Merton scholars and enthusiasts alike with yet another way to enter into the mind of this contemplative.”

“Harnetty’s vision here is immense... The work is distinctive, immersive, and poignant. It’s an unalloyed triumph and a magnificent achievement. Highly recommended.”

“There is a measure of restraint and care of spacing in the way [Harnetty] arranges these compositions, the way the piano melodies lead us gently through the pauses between Merton’s musings but also do not interpret them.”

“Brian Harnetty embraces such conflicts much as Merton did, and thus not only continues the conversation but opens it wider.”

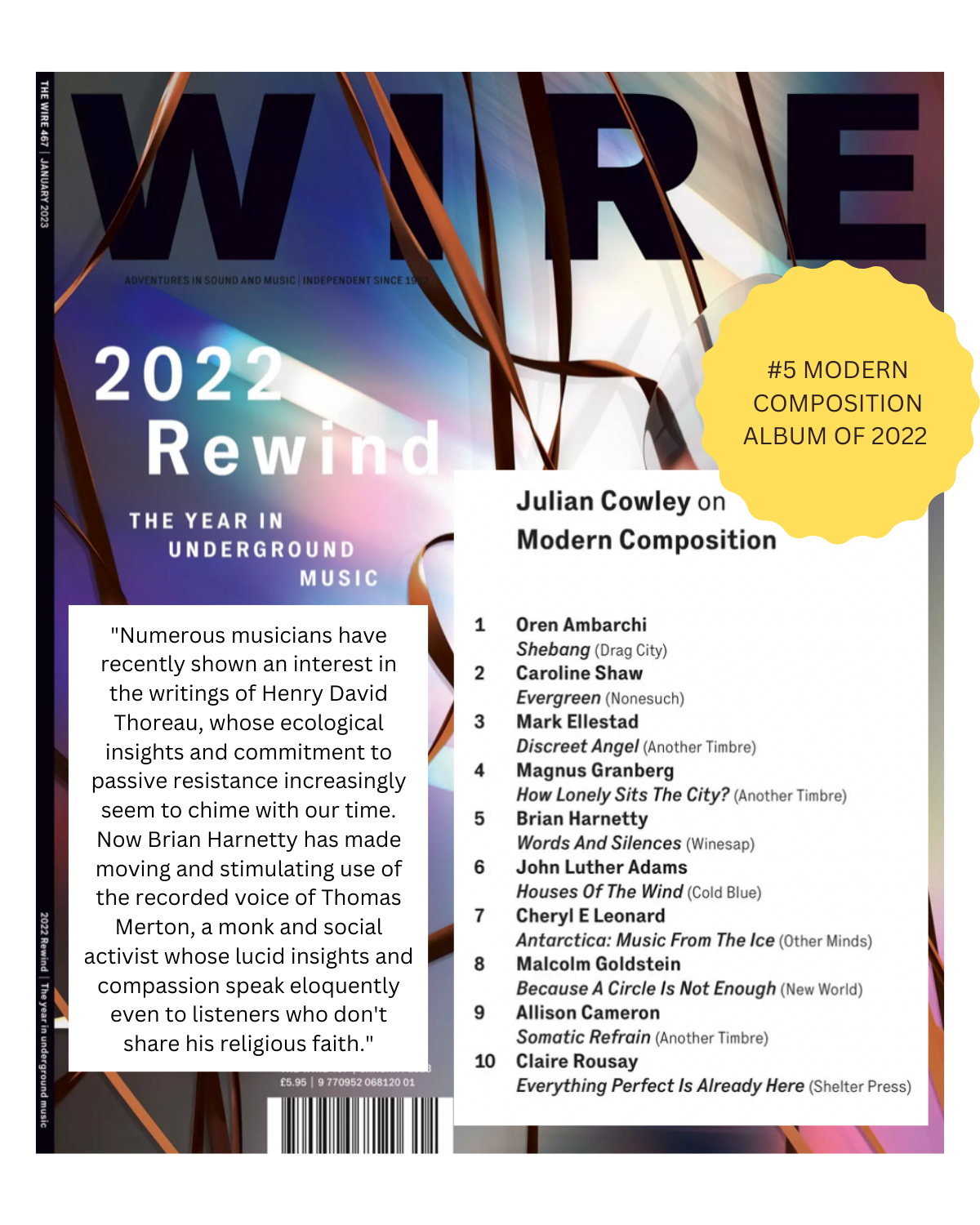

“Harnetty frames Merton’s humane eloquence with discreet and dignified music, realized on piano with a brass and reed quartet. The monk’s voice remains vital and apt; the settings are just right. #5 Modern Composition Album of 2022.”

“Harnetty’s work is an engagement, not only with thought and voice, but with intonation and emotion. Just as Merton often did other things in the silences: paint, draw, photograph – Harnetty decorates (not fills) the silences with music.”

“...the fragile sounds perfectly reflect the ineluctable sadness of mortality voiced by Merton... [Merton’s] humanity—as well as Harnetty’s sympathetic enhancements- gives me courage”

“It’s the best, most fully realized work yet from someone I don’t think has ever made a bad record.”

“Like most of Harnetty’s art, the Merton project harnesses the musician’s superpower of careful listening and his deep curiosity about other people. ‘It’s a way to open up what you’re doing and to be closer to the rest of the world,’ he says.”

“Harnetty advises us that we may adopt Merton’s sense of openness and playfulness, move between contradicting thoughts, hold them together, and listen as they melt into each other. It is an insightful and heartfelt homage to an inspiring mystic.”

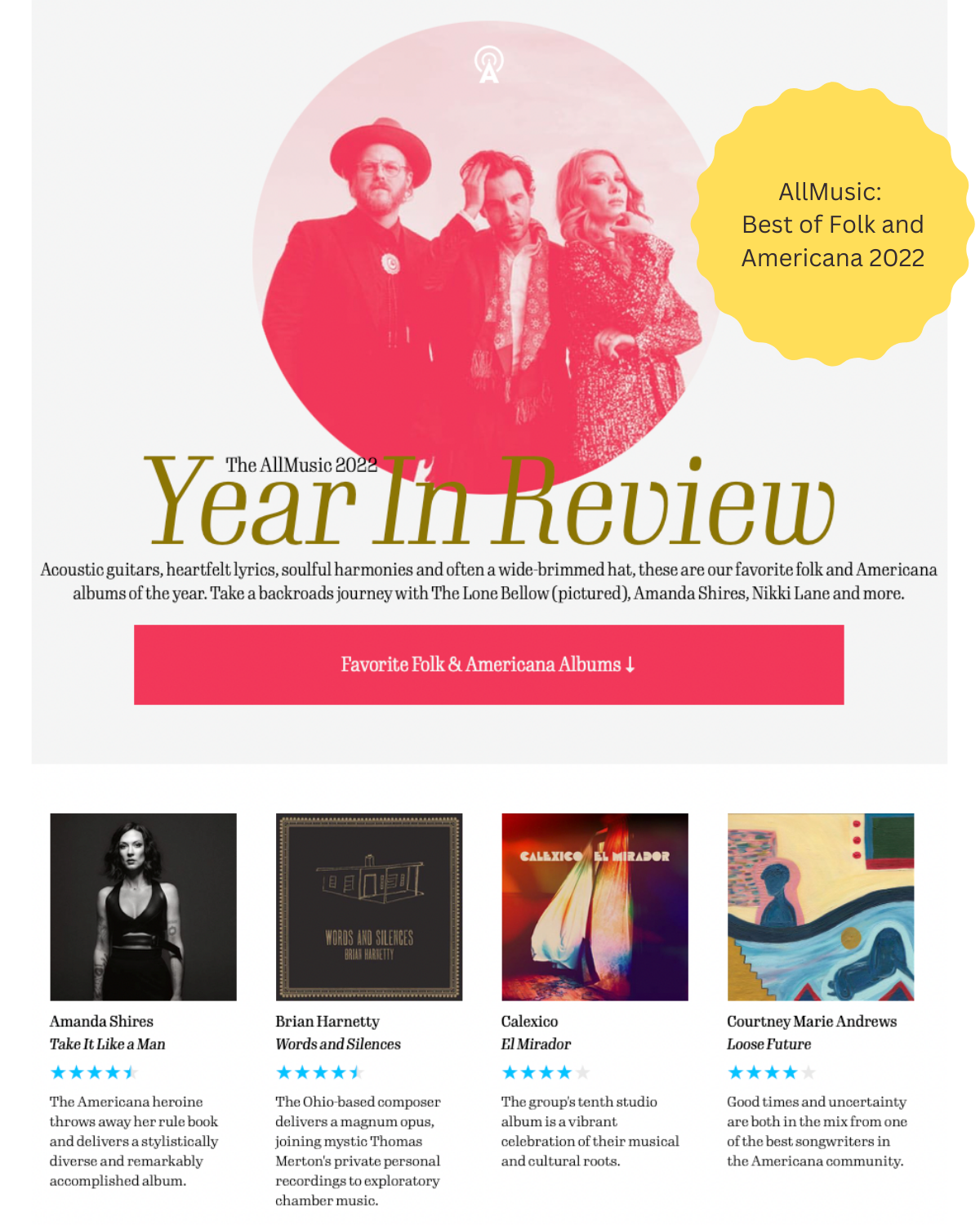

“The Ohio-based composer delivers a magnum opus... Harnetty reveals Merton’s acceptance of frustration, confusion, gratitude, and revelation as part of his journey — and hints it is also part of ours. Words and Silences is musically adept and emotionally and spiritually resonant. Brilliant. 4.5/5 stars. Best of Folk and Americana 2022.”

“This is one of the most fascinating works of recent times... with this work [Harnetty] reclaims my attention in a very poignant way. His ability to step back and put himself at the service of the words, to dive into them and then create music that sounds completely organized is beyond remarkable. A masterpiece!”

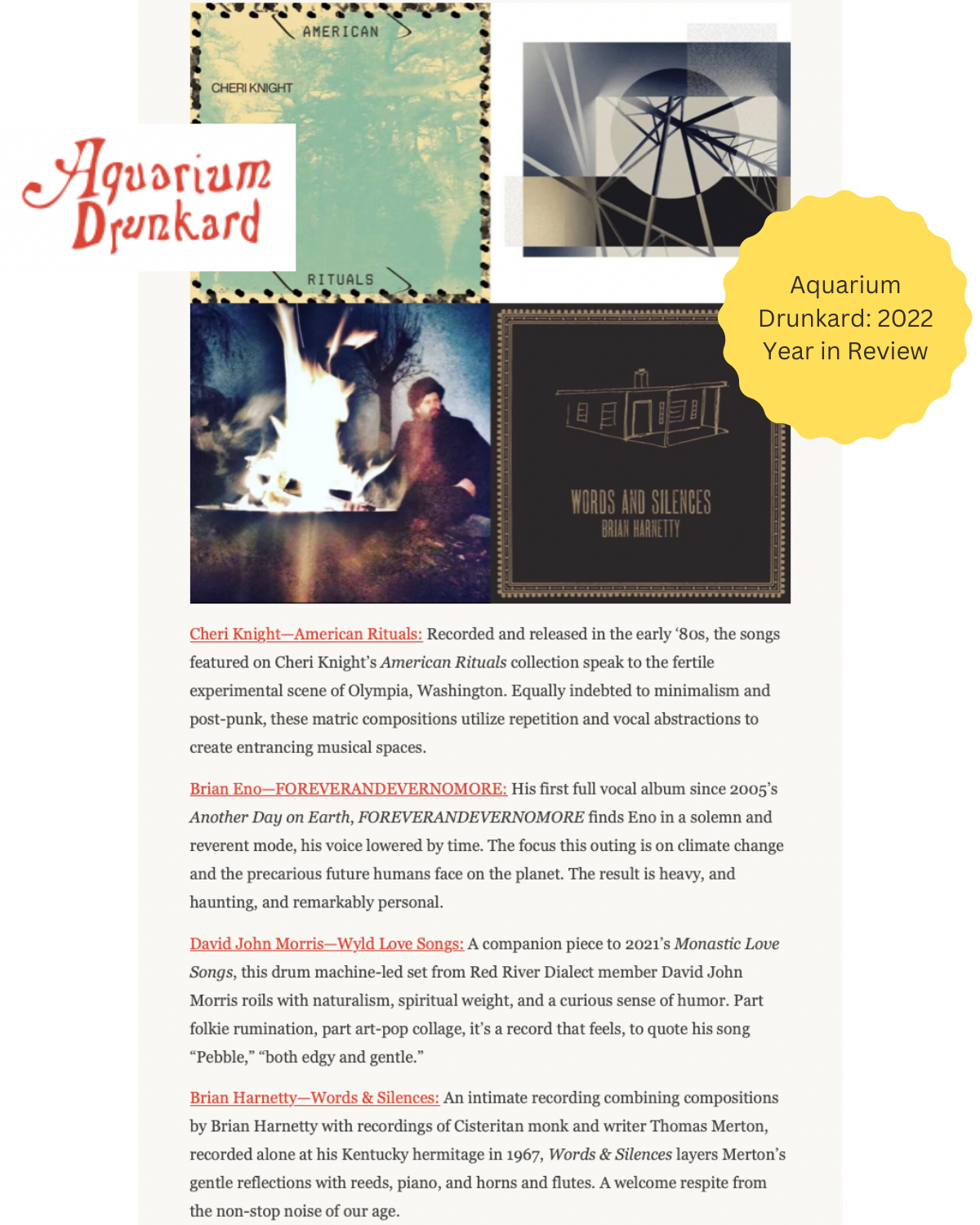

“A meditation and refuge from the incessant noise of modernity, the record offers harmonious balance between distinct spiritual forces, at work both individually and in multi-layered conversation.”

“Philosophical reflections...are evoked from the past through the powerful medium of music intelligently harmonized with the flow of words.”

“...in this world of haste... maybe this is the reflective wind-down for late evening listening when you can take time to think about your values and the demands the 21st century places on you and yours? Take the pause this offers.”

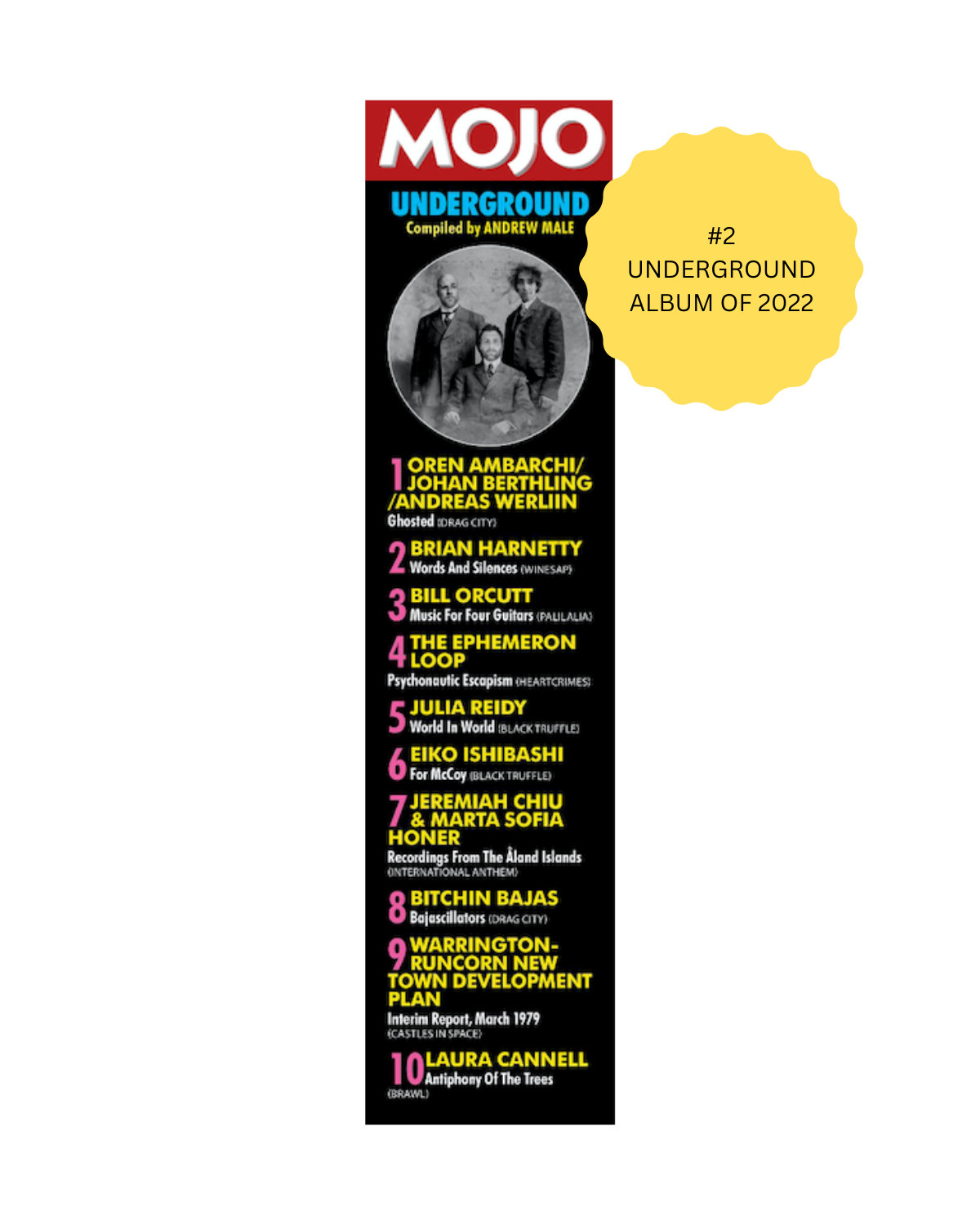

MOJO (UK)

“Reflective, vulnerable, melancholic and hypnotic, this is a record for times of solace, companionship and escape.” 5/5 stars — MOJO (UK)

For the past 20 years, Brian Harnetty has moved between the worlds of music and archival research, turning his ethnographic studies of the Appalachian people of Kentucky and Ohio, and his explorations of the El Saturn archives of Sun Ra, into works of abstract folk beauty. For this album, Harnetty has studied the works of Thomas Merton, specifically recordings made in Kentucky in 1967 in which the philosopher discusses everything from Beckett and Foucault to ever-changing natural surroundings of his hermitage. Subtly referencing Merton’s own music tastes (Mary Lou Williams, John Coltrane, etc), the subtle breathing patterns of meditation and the rhythmic sounds of nature captured on Merton’s tapes, Harnetty’s brass and wind ensemble craft a series of rising and falling musical conversations with the man. Reflective, vulnerable, melancholic and hypnotic, this is a record for times of solace, companionship and escape. #2 Underground Album of 2022. — Andrew Male

The Wire (UK)

On becoming a Trappist monk, Thomas Merton stopped wondering how to make his way through life and simply began to live. His prolific output in prose and verse found a home at New Directions publishing house. At the time of Merton’s death in 1968, electrocuted accidentally in Thailand, he was also well known as a social activist. Recordings of his warm, strong voice are heard on Ohio based composer Brian Harnetty’s Words and Silences. Merton responds to writing by Samuel Beckett and Michel Foucault, contemplates mysticism and perplexity, [and] deplores racial injustice in America. Harnetty frames Merton’s humane eloquence with discreet and dignified music, realized on piano with a brass and reed quartet. The monk’s voice remains vital and apt; the settings are just right. #5 Modern Composition Album of 2022. — Julian Cowley

Allmusic: 4.5 / 5 Stars

Composer and interdisciplinary sound artist Brain Harnetty employs field recordings, carefully sculpted textural and ambient electronics, musical instruments, and archives of spoken oral history and stories to reflect the communities connected to them. Words and Silences is a multivalent chamber work for quintet to accompany 1967 reel-to-reel tape recordings made by monk, mystic, and author Thomas Merton. Harnetty visited the Thomas Merton Center in Louisville in 2017. An archivist pointed to reel-to-reel recordings made alone in his hermitage at Kentucky's Abbey of Gethsemani. In them, Harnetty discovered an unfiltered, private Merton, experimenting, meditating, and digressing on birds, moonlight, God, music, violence, politics, doubt, Samuel Beckett, Michel Foucault, Sufi mystic Ibn al-Arabi, and more. He comments repeatedly on the tape recorder's form and function as his aid as Harnetty's intuitive, exquisite chamber music accompanies on disc one. The second disc contains only the instrumentals. An accompanying 48-page chapbook contains a lengthy essay by Harnetty and transcriptions of the taped material.

On "Sound of an Unperplexed Wren," Merton begins at the beginning: "Ok, now I hope we can go on recording like this, I think it will stay down. Let's go." His voice speaks the title, and he follows with "no comment necessary" before listing bird species. Harnetty weds repetitive piano with clarinet and flute as subtle brass, percussion, and winds frame Merton's words. "A Feast of Liberation" is an experimental meditation. Recorded at night against a background of jazz, he moves between the subjective and the objective on the race riots occurring across the country. That the night is quiet and that people are being killed elsewhere. A lone piano playing a four-note pattern is joined by a clarinet, then expands the theme. Merton's voice returns, commenting on the night's atmosphere, and shooting sounds from nearby Fort Knox. Throughout, Merton references the tension and uncertainty existing between his humanity and his vocation, his solitary monastic life and the desire to interact with the world, before extrapolating them into expansive metaphysical questions. In "Breath Water Silence," the morning sound of monastery bells during lauds frames his comments about Ibn al-Arabi's conception of God, underscored by a drastically slowed piano transcription of Meade Lux Lewis and Albert Ammons' "Boogie Woogie Prayer," before ruminative, gospelized horns flow in and out with Merton's narration. In "New Year's Eve Party of One," he references pianist Mary Lou Williams amid tape hiss and sounds of a December night as Harnetty quotes from her Zodiac Suite. (Elsewhere, Merton references Louis Armstrong, John Coltrane, and Buck Owens -- Harnetty offers impressions of them all.)

Words and Silences embraces the mystic's many contradictions in reflecting his embrace of "authentic perplexity." Merton relentlessly sought a unifying discovery to resolve contradictions in human life, spirituality, love, nature, violence, and the cosmos (inner and outer) that was just out of his reach. Harnetty reveals Merton's acceptance of frustration, confusion, gratitude, and revelation as part of his journey -- and hints it is also part of ours. Words and Silences is musically adept and emotionally and spiritually resonant. Brilliant. Best of Folk and Americana 2022. — Them Jurek

Aquarium Drunkard

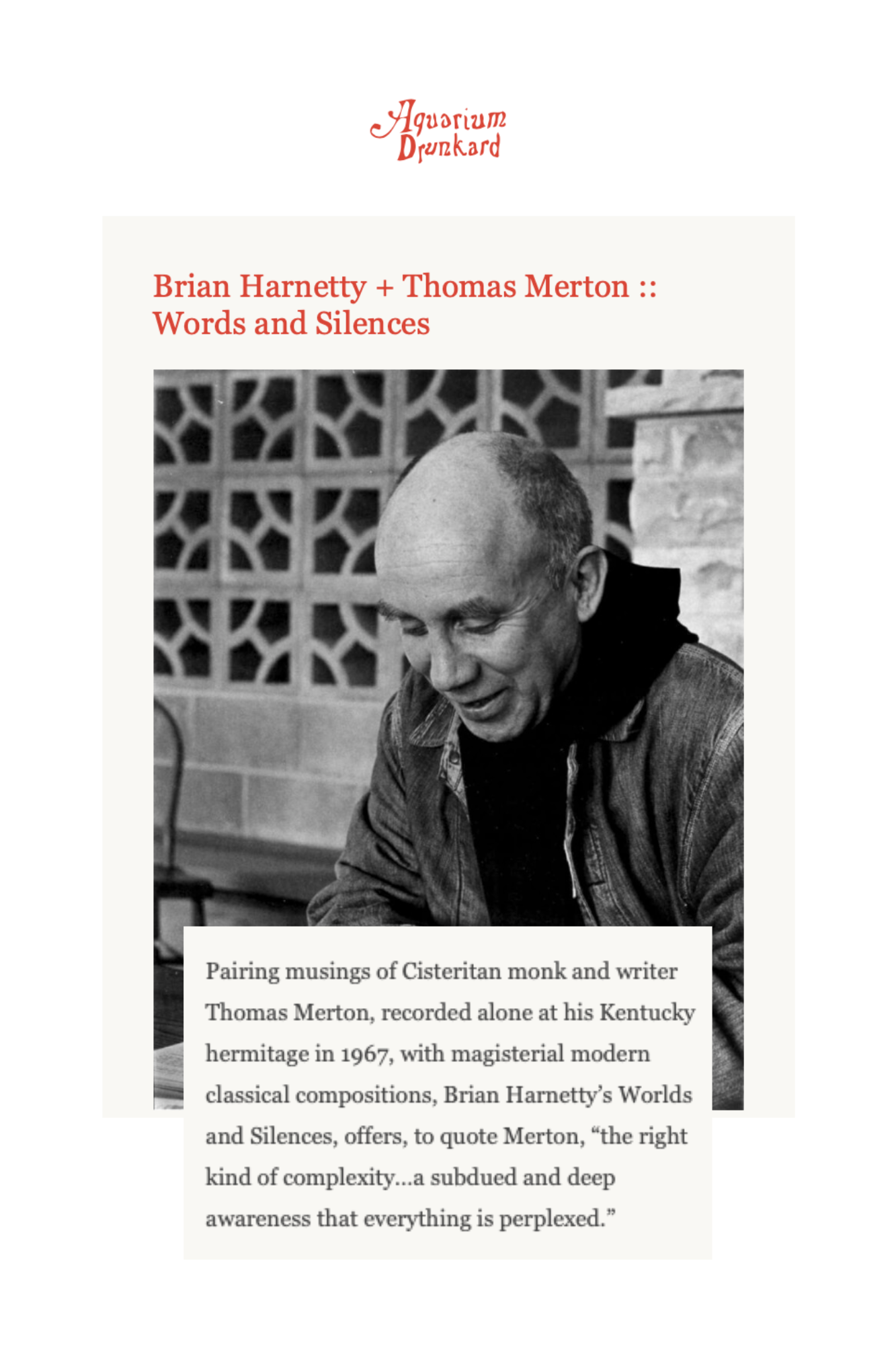

Pairing musings of Cisteritan monk and writer Thomas Merton, recorded alone at his Kentucky hermitage in 1967, with magisterial modern classical compositions, Brian Harnetty’s Words and Silences, offers, to quote Merton, “the right kind of complexity…a subdued and deep awareness that everything is perplexed.” … Along the way, Harnetty and co. melodically nod toward cherish artists from Merton’s own record collection, including Jimmy Smith, Joan Baez, Buck Owens, Louis Armstrong, and John Coltrane, maintaining a calming, curious tenor throughout. A meditation and refuge from the incessant noise of modernity, the record offers harmonious balance between distinct spiritual forces, at work both individually and in multi-layered conversation. 2022 Best of / Year in Review. — Jason Woodbury

A Closer Listen

Words and Silences is released in dual vocal and instrumental versions, befitting its title. Winesap Records is also offering a fine 48-page chapbook, which we recommend to gain that precious tactile experience. While Thomas Merton ~ the subject of this album ~ was a mystic, monk and nature writer, we can’t help but think he would have preferred a physical book to a digital copy.

The listening order will influence one’s interpretation. Play the instrumental version first, and later one may hear the words as an amplification, finding spaces one did not know existed. Play the vocal version first, and later one may feel as if something more than words has been removed ~ or conversely, that the echo of the words continues to exist in the notes.

We’ve tried both, and recommend the former. The label writes, “This music is great for driving, looking out of windows, quietly sitting on the front porch, walking across fields and forest paths, and careful up-close listening.” It’s also a perfect accompaniment to the chapbook, because it is nigh-impossible to read while listening to narration. And while the words of Merton are the most important part of the release, the replay value of the instrumental version is much higher. One may even imagine time folding back on itself, the monk alone in his hermitage in 1967, recording observations on a reel-to-reel recorder. It’s likely that his musings first appeared in handwritten form, notes scrawled while listening to John Coltrane, Louis Armstrong, Mary Lou Williams and others, whom Brian Harnetty quotes in his music. While the brass and wind instruments are intended to evoke meditation, they may also suggest nature, aspiration, and the passage of time. Harnetty’s piano provides the anchor for these compositions, but the music soars whenever the brass quartet enters, inspiring the listener to believe that with a little help from each other and above, Merton’s societal dreams might one day come true.

The connections continue on the reel-to-reel disc. Merton’s words and silences create space for contemplation, each pause an opportunity for musical or spiritual reflection. After visiting the hermitage, Harnetty retreated to “a temporary hermitage” of his own, playing the tapes until they began to seep into his soul. He concluded that they formed a portrait of Merton’s interior life, one that with a bit of molding might become a radio-play, but that he would present in a more abstract manner, preserving the field recordings, beginning with an “unperplexed wren” and occasionally sharing the “peripheries” rather than the heart of the monologues.

Merton seems fascinated with the recording process, enamored with the mechanics. The reel-to-reel recorder provided him with a way to interact with his thoughts and his own voice; Harnetty’s work is an engagement, not only with thought and voice, but with intonation and emotion. Just as Merton often did other things in the silences: paint, draw, photograph – Harnetty decorates (not fills) the silences with music.

One of the most telling passages in Harnetty‘s musings is his reaction to being in a deserted cabin in winter: “I have the desire to fill the cabin with sound: radio, music, anything that could be a distraction from settling down with my thoughts and this unceasing, noisy silence of being alone.” This passage echoes Merton’s “experimental meditation, against the background of some jazz,” as well as a New Year’s Eve spent alone playing records. By making two recordings, Harnetty fills the silences with music and removes the words to reveal silences. By writing a chapbook, he imitates Merton’s creative process in such a way as one might use Harnetty’s words as the basis of a new composition.

Harnetty listens to Merton, who quotes al-‘Arabi and listens to Mary Lou Williams. Merton writes of racial unrest in Louisville; Harnetty thinks of Floyd. Who am I who sit here? As time markers disappear, Harnetty concludes, “the opposites of the world melt into each other.” When identities are subsumed, the possibility for forward progress is revealed, the “I” giving way to the “we,” a conclusion ironically discovered in the midst of a solitary life. — Richard Allen

The Merton Seasonal

To know the man Thomas Merton, one must begin to immerse oneself in his own contemplative world. Merton enthusiasts and scholars often do this by exploring Merton’s primary sources, for instance The Seven Storey Mountain, his journals and any other of his numerous publications. Merton also provided the world with a large number of photographs and drawings, in which one can appreciate Merton’s keen artistic insight into the world. Finally, the various series of published recordings of Merton’s conferences and taped reflections over the years provide an opportunity to sit down and listen to the very voice of Merton. Brian Harnetty’s new project, Words and Silences: From the Hermitage Tapes of Thomas Merton, provides the world with a unique and novel variation on this last source of Merton material.

Harnetty, an interdisciplinary sound artist, is known for his creative integration of media, including words, music and sound. The goal in such a hybrid compilation of sounds is to foster a metanoia, or change in the listener. Words and Silences, which integrates Merton’s voice and original musical compositions by Harnetty himself, fosters an opportunity for such a change in those who immerse themselves in the project. What results from this process is a “sonic portrait” of Merton. This portrait consists of a delightful conversation between Merton and the music, where both work together to help bring the listener into a deeper reflection of God in the world.

Harnetty creates this sonic portrait by first exploring archived recordings by Merton from 1967. These recordings, made at his hermitage, begin as an experiment. In the track entitled “Thinking Out Loud in the Hermitage,” the listener hears Merton’s own initial suspicion of this technology, specifically in how such a device can be effective in communicating the true, authentic self. But as each track progresses to the next, the listener witnesses Merton’s evolution in understanding the uses for the tape recorder. What begins as an experiment becomes a medium for meditations on peace, justice, music and more. Harnetty has skillfully chosen excerpts, from an undoubtedly large amount of available audio material, which perfectly encapsulate the humanity of Merton.

In addition to these recordings preserving the voice of Merton, the contexts of the hermitage has also been preserved. In the introductory track, “Sound of an Unperplexed Wren,” the listener hears several birds as they fly by, unknowing that their song was being recorded for posterity. In “Feast of Liberation” there is a subtle, almost eerie clock ticking away in the background, as Merton reflects on the Louisville race riots, which were happening at the time of the recording. To listen to these recordings is to be transported back in time. Harnetty has given the listener an opportunity to fully be present in the room with Merton, as he experiments with this new technology.

Merton’s voice and the sounds of the hermitage are but two of the contributors to this sonic portrait. While Merton may have been alone in his hermitage at the time of the recordings, he spends his time reflecting on voices of wisdom figures, philosophers and mystics that inspire and challenge Merton. In “Let There Be a Moving Mosaic of This Rich Material,” Merton reflects on Michel Foucault’s then recent publication Madness and Civilization. On this track, Merton and Foucault become conversation partners, with a lone piano musically knitting the conversation together. Harnetty balances the complexity of the conversation with a simple melody that draws the listener into the heart of the mosaic. Many of the other tracks feature the wisdom of Sufi mystics, jazz musicians and contemporary writers of Merton’s day; but there are also tracks that feature Merton’s own poetry and reflections, as if he is carrying on a conversation with himself.

While the skillfully selected archival recordings are a highlight of this project, Harnetty’s process of orchestration and production of the music is equally brilliant. When he began the project, Harnetty did not know what the finished product might be and as he continued to listen to the recordings he began to imagine a play, where the music and Merton exchange particular parts. Throughout the selected recordings, Harnetty observed Merton’s own improvisational style, commenting that at times, Merton seemed to be improvising an entire recorded selection. Inspired by this improvisational style, Harnetty began a process of creating orchestrations based on some of Merton’s favorite music. First he chooses a particular phrase from a larger piece, for example, “Boogie Woogie Prayer.” He then manipulates this phrase in a number of ways, by changing tempo, octave or rhythm. What results is an improvisation of word and music that is featured on the track “Breath, Water, Silence.” Harnetty uses this method for other tracks as well, using three notes from John Coltrane’s “Ascension” to accompany Merton’s voice during “Feast of Liberation.” The improvisation process is taken a step further with the actual performance of the orchestration. When sharing the composition with his group of four other musicians, Harnetty gave them a guide to follow and the musicians were invited to record several versions of each track, independent of the other instruments included in the ensemble. Once these tracks were completed, Harnetty wove all the tracks together, blending in Merton’s voice, to complete the sonic portrait. The result of this hybrid of media is a beautiful, soulful and at times complex conversation between Merton and the music, sometimes each speaking alone, sometimes both speaking together and sometimes inviting others into the conversation.

Today, the tape recorder has become all but extinct, replaced first by compact discs and eventually by digital media. Harnetty, by harnessing the beauty of the grainy recordings, has given new life to these previously little-known words of Merton. By integrating his own musical orchestrations into Merton’s recordings, Harnetty provides Merton scholars and enthusiasts alike with yet another way to enter into the mind of this contemplative.

Words and Silences contains 22 audio tracks, eleven tracks with Merton’s voice and music and eleven instrumental tracks that highlight the musical compositions alone. In addition, there is an accompanying booklet that contains Harnetty’s essay on the project along with transcriptions of the recordings. Words and Silences is published by Winesap Records and is available via Bandcamp in both streaming and downloaded versions, as well as on CD with accompanying printed text. — Julianne E. Wallace

Dusted Magazine

Composer and instrumentalist Brian Harnetty has accomplished something rare in Words and Silences. He has achieved a compelling, an oddly timely synthesis of the recorded reflections of Thomas Merton and Harnetty’s own limpid music. Merton, the Kentucky-based Trappist monk who achieved a halting fame in the mid-20th century, recorded a series of reflections in 1967, the year before his unexpected death in Thailand. These are fundamentally reflections on those things noted in Harnetty’s title, but also on books and identity and nature. They are not overly self-regarding or verbose, and it’s that sense of sparseness and gentle clarity that Harnetty’s music also possesses…

In [these] fractious times, I found myself not just compelled but consoled by this music. Harnetty’s writing is pure, though never necessarily hymnal, and Merton’s generosity of spirit and his candor can be a balm. Whether he discusses Mary Lou Williams or Michel Foucault, he is invariably drawn to what lies outside of himself: the hawk waiting by the cross in a poplar tree, on the morning of Pentecost; or the idea of examining fragments, seeing not just difference but the possibility of making mosaics. Harnetty is to be commended for writing such gorgeous music, and for realizing such a project. — Jason Bivins

Columbus Monthly

As a teen, Columbus composer and sound artist Brian Harnetty got his hands on a couple of books by Thomas Merton, a progressive, Cistertian monk who writings in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s tackled topics like pacifism and interfaith studies. Harnetty was drawn to Merton’s dual identity as a mystic and an activist who spoke out on issues of race and the Vietnam War.

Despite Merton’s ordination in the Catholic priesthood, he validated other religious traditions. “I used Merton as a way to gently discuss and argue about religion with my parents,” Harnetty says. “That was an important step for me as a teenager.”

Harnetty set Merton aside for a while, studying at the Royal Academy of Music in London and Ohio State, later earning his doctorate at Ohio University, where he focused on sonic ethnography and sound art. Over the years, Harnetty has worked with the Berea College Appalachian Sound Archives and the Sun Ra/El Saturn Archives in Chicago to create albums, sound installations and performances that feature his own musical compositions interacting with archival audio.

Several years ago, Harnetty began to wonder what treasures might be tucked away in the Thomas Merton Archives at Bellarmine University in Louisville, so he ventured down to Kentucky in 2017. Most of the audio featured Merton’s lectures, but Harnetty wanted something less public. “The archivist said, ‘There’s this other set of tapes that he made in his hermitage that you might be interested in. They haven’t been published.’” Harnetty says. “I knew they were what I was looking for.”

In 1967, a year before he died, Merton experimented with private, journal-like recordings, pontificating on everything from Samuel Beckett and Sufi mystics to the racial uprisings in nearby Louisville. “Merton uses his tape recorder as a contemplative tool, but he’s also investigating what the medium is and what it means,” Harnetty says.

To compose music to accompany Merton’s words, Harnetty made a playlist of music Merton loved, including jazz and boogie-woogie. Using that materials as a jumping-off point, Harnetty began composing, playing piano and recruiting trusted musicians to add clarinet, saxophone, trombone and trumpet. He wrote the meditative score in the early days of the pandemic—a period that complemented Merton’s hermetic world. The resulting album, Words and Silences, releases on Oct. 7, and on Mov. 9, Harnetty and his chamber ensemble with premiere the project at a Wexner Center show in Mershon Auditorium, which will also include video footage of Merton’s hermitage.

Like most of Harnetty’s art, the Merton project harnesses the musician’s superpower of careful listening and his deep curiosity about other people. “It’s a way to open up what you’re doing and to be closer to the rest of the world,” he says. — Joel Oliphint

Some “Best of 2022” Lists for Words and Silences from online and radio:

The Wire: Contributor's Charts (Julian Cowley) 2022

Dublab: Morpho—Graph Paper: Best of 2022

Screen of Distance: Best of 2022 Records

Independent Clauses: Top 10 Albums of 2022

No More Workhorse—Boa More: A Year of Music

Byte FM Radio (Germany): Best of 2022

David Mennessier: 150 Recordings of 2022

There Stands the Glass: Top 25 Reimaginings of 2022

iCatFM Radio (Catalonia): Best of 2022 (International Music)

Aquarium Drunkard: Dao Strom and Brian Harnetty: In Conversation

Brian Harnetty is an interdisciplinary composer/sound artist whose projects bring together place, myth, history, ecology, and economy. Informed by his family’s roots Appalachian Ohio, his 2019 project, Shawnee, Ohio utilized archival recordings alongside newly composed music to create a series of audiovisual portraits of people from a small Appalachian mining town, was named MOJO Magazine’s “Underground Album of the Year.” His latest project, Words and Silences, is a musical portrait of the Cisteritan monk and writer Thomas Merton, bringing together archival recordings Merton made alone in his Kentucky hermitage in 1967, along with newly composed music, to create a long-distance, intriguing exchange between Merton’s intimate tape-recorded contemplations and the contemporary moment.

Dao Strom is a poet, artist, and songwriter who also makes multimodal projects that explore “voice” at the intersection of text, image, and music. She is the author of five books and two song-cycles, most recently the poetry collection, Instrument (Fonograf Editions, 2020), which blends poetry and images, and the book’s companion music album, Traveler’s Ode (Antiquated Future Records, 2020), an interwoven series of textured, ethereal “song-poems” that explore themes of displacement, diaspora, and hauntings. Born in Vietnam, Strom grew up in the Sierra Nevada foothills of northern California, and draws from disparate “folk” music and poetry influences—from rural American gospel ballads to Vietnamese “sung-poetry” (ca dao).

In this conversation, Harnetty and Strom talk about how the intersections of sound, language, music, memory, history, place, and practices of “listening”—to the past, to the present—fuel their respective interdisciplinary practices. Although working in quite different contexts, both artists root their art in a strong contemplation of place and one’s relationship to “place”.

Dao Strom: Hi Brian, how are you today? What kind of day is it where you are?

Brian Harnetty: Today is filled with a lot of busyness––more than I’d like––of parenting, work, meetings, cooking, and so on. Enough that I can’t seem to focus on any one thing for long. Still, I stole five minutes to be quiet today. I’m also thinking a lot about hydrophones…We had a fire outside last night, and I can still smell the smoke on my hat, and I like that, too. How about you?

Dao Strom: I am sitting on my couch in Portland, Oregon. There are crows gathering on the lawn across the street and sometimes a squirrel runs by my porch. I am trying to root myself in the concrete as I start to think about our two projects because whenever I start to think about music, I also start to think very abstractly about place, I start to think about music—the space of a song, for instance—as a nonphysical place. I think our two projects are very different, yet there are elements and maybe some methods in common, maybe some similar veins we’re traversing. There are the hybrid and interdisciplinary elements, of course, the way these projects don’t fall completely or neatly into the expected “genres” or “disciplines” we each might’ve begun our practices with; but I think we may also have in common things like working with time and ghosts and remote collaborations (multiple voices, archives, etc). Words and Silences is in essence a dialogue with Merton’s recordings, but also an odd, asynchronous dialogue across time-space, so maybe too it is a dialogue that attempts to fill in or connect the silences, connect solitudes? I wonder too about how place—the regional geography you roughly share with Merton—underpins this project? Are you dialoguing with “ghosts” when you compose music in response to archives from the region where you live?

Brian Harnetty: Incidentally, your concrete and careful description of what is in front of you, and of nature in particular, is exactly how Thomas Merton begins most of his tapes and journal entries. And I always love these moments the most; they are a simple and grounded way of paying attention, a balance to abstraction.

But to start answering your questions about place: for a decade, I have been focusing almost exclusively on the town of Shawnee in Appalachian Ohio, and yet I don’t live there. I travel back and forth between Shawnee and my home in Columbus, and in that process everything gets mixed up. My grandfather is from Shawnee, yet he died long before I was born. Sometimes I think my desire to be in and make pieces about Shawnee, its buildings, and streets, are as physically close as I can get across time to meet him—a ghost, for sure. So, the place and the idea of a place are fluid, and they seep into one another. Shawnee has changed me. It has changed my work, even as an outsider. And in some small way I may be changing it, too.

What about you? How do you connect place, time, silences, and ghosts? Obviously I see it in the extreme physical distance between where you were born and where you live now, and the time in-between. I also see it in the “silences” of Instrument: the physical spaces between words and punctuation. Or the repetition and returning and reworking of themes, traveling back and forth between them, bringing out something new with each journey. And then the photos, too: often empty of all people, and when there are others, including yourself, they are out of the frame, or fragmented, partial. And it is all very concrete: crossing the river, the tiny birds, the yellow dress, the caves.

Dao Strom: When you say that your grandfather was from Shawnee but you actually never met him, and that the project of immersing yourself in that place (now physically absent of him) is a means of getting closer to him, I definitely see correlation between our methods…I was born in Vietnam but have no memory of it. In my life I’ve met only one grandparent, my mother’s father, briefly once before he died. My own father is still alive, I’ve met him only a handful of times, and communication is difficult also because I don’t speak Vietnamese.

One of the “place” processes that fed into Instrument was that I wanted to visit a certain location in Central Vietnam, a stretch of highway where a certain event occurred in 1972, a tragic event, a massacre. Sadly, many events of this nature occurred in those war years, so the significance of this event, for me, is not historical investigation so much as it has simply to do with the fact that my parents, as journalists, visited this site exactly nine months before I was born. In my perhaps naive way of thinking, I imagined this location, this event, as a key part in what they shared—their bond (probably too their shared sorrows) at the time—and hence a sort of emotional backdrop to my own being.

I had a question in mind, or maybe more so in my body, about ghosts, in visiting that region of Central Vietnam. I was wondering, would I feel them, would I hear them, would I feel something in being there, physically? I often come away with more questions than answers, with these processes. There is a small memorial at that highway site, the only evidence of the event that happened there, and I recorded the sound of some metal chimes clanging above the altar there. This sound got woven into a track on the Traveler’s Ode album (the “Wading into a new decade, etc” song), which also contains sounds from the jungle and a cave I visited in that same region. The caves in that region have been a fascination of mine for some years now–the idea of this vast system of karst caves (far more vast than tourists get to experience), the idea of a whole ecosystem uniquely preserving itself beneath and despite all the human activity wrecking its surfaces; this contemplation has given me a lot, in way of realizing and healing my own sense of Vietnam and whatever losses my parents may’ve felt standing on that stretch of highway in 1972. Collecting those few field sounds to work into a song is my small way of trying to piece together some of these thoughts and feelings.

Brian Harnetty: It is increasingly clear to me how much you connect the body—in terms of sense, of affect—to both place and past, physically putting yourself there to see what you feel. And yet the past can’t be touched, we can only catch glimmers of it, reverberations, aftershocks. Maybe this partially points to your interest in music and sound: sound physically touches us and at the same time moves through and around us. And to pinpoint your own origin like this, forged through the bonds and sorrow of your parents, it shows how much the past can affect us in profound ways, but it also can be a heavy and lasting burden to carry. But I also wonder if the process you go through might actually work toward acknowledgement, letting the past touch you but also letting it pass through?

Dao Strom: Yes, certainly, that makes sense, too. I’m enmeshed in the past but at the same time have a desire to make art that might also transmute or transcend some of those burdens—in the end, at heart, I’m definitely trying to do something other than just document…

While your Shawnee, Ohio project is very much anchored in a geographic place, your Merton project is more of a specific dialogue, a collaboration with the voice of Thomas Merton, via his taped vocal archives. This is a different kind of “ghost” communion, isn’t it? How does “place” figure in with the Merton project? Might the voice, his words, in this case, be also a form of place?

Brian Harnetty: For Words and Silences, the connection is through words, and the archival recordings. I haven’t been to Merton’s hermitage, yet. So it is in my imagination. I have looked at every photo I can find, memorized the interior, imagined sunlight through the window, the warmth of a fire against the coldness of cinder block walls. There are clues in Merton’s recordings, too. You get a sense of the room; there is an ever-present ticking, perhaps of a clock; the gas turns off. And outside he records birds, rain, thunder. There are aural clues in his journals, too, often of nature. So, I am piecing all of these things together, making speculative connections, assembling it into a different and subjective whole.

To make the album, I listened to and transcribed many hours of Merton’s recordings. And then, after I narrowed down exactly what recordings I wanted to use, I listened to them dozens, maybe hundred of times. At some point, I felt so close: I started to think no one has been this physically close to him in over fifty years (Merton died in 1968). I even began to think of us as friends. Every inflection of his voice, breath, hesitation, laugh––they all hold meaning to me, they betray his humanness and vulnerabilities. I felt an intimacy, one that comes from countless hours of dialogue. And yet, he is not listening to me. It is one way. So yes, this is exactly how I would describe visiting a ghost; a recorded shadow of a man. This has happened many times with other projects, too.

Dao Strom: That is a very immersive research process, and I admire the patience in it. Might I ask what led you to this song-form, of creating time-space spanning dialogues between archives and your own compositions? What led you to this form of your musical voice (piano) conversing—years distant—with the voices of others, from recorded archives, captured on tape?

Brian Harnetty: When I was a student, I tried to make music that recreated the spontaneity I heard in field recordings: the texture of people talking, untrained singers, the sounds of places, and so on. I made increasingly complex scores, and it never felt right. Later, I gave up and started working directly with recordings––old and new, archival and field recordings––and everything changed. I saw that the recordings themselves contained things that couldn’t be recreated without losing something. Not only the grain of the voices, but also in-between and peripheral moments that created a rich and complex world if you only listened to it with different ears. Then, when I began working with formal sound archives, everything changed again: I started to meet relatives of people who were on the recordings, and suddenly there was a physical connection between past and present, between the dead and their families, with the recording acting as a medium between them. It changed the way I understood sampling, and breathed life into otherwise dead archives.

The Merton project is a continuation of this process—eavesdropping in long enough to feel close, as close to time travel as one can get. And yet, and this is important, not doing so with a sense of sentimentality or nostalgia. Instead, to make something new of the material, to step back and understand how old recordings might be relevant today, how they might act as cautionary tales, or in Merton’s case, how his use of both contemplation (silence) and action (words) might help us address racial and environmental justice issues.

I, too, want to ask you about voice, and about the physical mediums you are using. I am thinking both in terms of your singing voice (and how you recorded in such a large and resonant building, for example [for the “Traveler’s Ode” song]), and your written voice. In Instrument, you mention learning techniques about a given medium––photography, audio recording, and your development as a singer and musician––and how this process of exploring and mistakes yielded new ways of understanding. I was surprised to see this folded into the text, but it makes sense, and felt very honest to me. It also seemed to reiterate in-betweenness: between place, culture, time. In the Merton tapes, I heard him doing something similar: he was interrogating the medium of tape, grappling with what it might reveal and what it hides, and ultimately using it as a tool for contemplation.

Dao Strom: This concept of mistakes being part of the fabric of the work, makes me recall some short films by an artist named Sky Hopinka, where in some shots the camera will jolt or tilt or go black suddenly, and you realize he has made edits that intentionally show the “seams” of the camerawork. This, I think, is similar to the “grain of the voices” (such a great phrase) that you speak of, and the wish to capture those peripheral and spontaneous moments that lend a special texture, that is also unreplicable. Does working with these types of materials become, thus, a sort of working with, composing around, leaving in, of the spaces in-between, I wonder?

Brian Harnetty: Yes! The “grain of the voice” is a phrase by Roland Barthes, and my expanded understanding is that the spaces and silences of a recording also share a kind of audible “grain”––one connected to memory and place, much like photographs––that I want to pay attention to, to highlight, and to ultimately place at the center of the work.

Dao Strom: I love that. I’ve drawn a lot from Barthes in regards to contemplating image, too…In regards to voice: I think maybe, especially with this latest project, I needed to find the “spaces” (or happen on them) that could best enable the voice, both written and sung. By this, I think I am trying to say that the voice—in best expression for a song or poem—may need a certain context or space to sound within; its precise cavity, or body. With the “Traveler’s Ode” song, for instance, I had sung it many, many times before and even tried to record it in a few instances, it’s actually a song I wrote and recorded as an a capella version many years ago; but this incarnation of it, singing through effects pedals, came together as a recording only once I’d found that cooling tower space [in the abandoned/re-purposed Satsop Power Plant]. Once I decided on the slightly hair-brained idea of recording in that space, the pieces fell together quickly, in terms of logistics and collaborators and timing. It was as if that was the place the song wanted to be recorded in. With the poetry, though, as in those self-reflective and transparent passages you mention in Instrument, I would say the ‘space’ of those “voicings” was a very interior space. Some are fragments culled from what I might call my personal journals. I don’t really keep a diary-fashion journal, but I do have several documents on my computer where I write very organically and associatively to myself (or for myself). I think maybe some of the energy of those initial spontaneous voicings provides some of the “grain”, if you will, of voice in those parts.

While you are not nostalgic in working with archival recordings, as you say, I think you are also quite respectful in the way you allow the archival voices to take space, to express their own rhythms and cadences; how you seem to try to stay out of the way and not guide our interactions with them (although, by nature of curating and selecting, you are guiding us). Nevertheless, there is a measure of restraint and care of spacing in the way you arrange these compositions, the way the piano melodies lead us gently through the pauses between Merton’s musings but also do not interpret them. In the “Let There Be A Moving Mosaic of This Rich Material” track, there are some wonderful, riveting lines from Merton that speak to just this sort of thing — getting out of the way, letting the “material speak for itself”, and so forth. To briefly quote, he says: “instead of polarizing, to make mosaics of all the material that is there, to take the material as it is. Natural and social. Not pass final judgement on it, not try to stabilize. Let there be a moving mosaic of this rich material.” (And then he moves into an even more meta space, reflecting on his own medium: “And perhaps tape can help to do this.” Which has such a wonderful, almost innocent aura of questioning to it.) I think some themes of both Merton’s contemplation and your process are captured in those lines. What you are doing with this album feels, to me, very much about the “natural and social” and enacts the “mosaic”, too. Do these qualities resonate with you, the natural, the social, the mosaic? I’m also curious about how you arrive at your own voicings, in terms of the piano sections and where/how they occur. Do you assemble the archival voice passages first, or your piano parts?

Brian Harnetty: Yes, that passage where Merton talks of a “moving mosaic” was a both guide for me and a key for the entire project. I tried to keep the integrity of the archival recordings by leaving them (mostly) alone, but at the same time I am cutting them up in relatively large chunks. And I see the album––as a whole––as a collaged mosaic. The same is true with the music: built from fragments of transcribed recordings that Merton loved throughout his life, I then collaged those together too, and let the material shift and change without adding any tricks or “development.” Essentially, I took Merton’s advice to get out of the way and leave the material alone.

So, yes, I always begin with the archival recordings, along with some kind of research (here, finding and transcribing Merton’s words and favorite music). I also think it’s important to consider the historical and cultural contexts of the recordings, along with a sense of stewardship to those recorded. And as I said earlier, I spend most of my time listening to the recordings again and again, noticing what I am attracted to, what elicits an emotional, visceral response. Only when I can’t stand it anymore (and I am waking up in the morning with the recordings playing through my thoughts) I begin to arrange and bring everything together. It’s all rooted in a particular way of paying attention: careful and critical listening.

Perhaps as a way to finish, I would like to ask: how do you imagine someone experiencing your projects? I can say that as I move back and forth between Traveler’s Ode and Instrument, not only am I focused on the interplay between text, image, music, and voice, but they share a combination of intimacy and quietness that invites me to take a second look, to lean in closer, straining to hear, coming back to reread phrases that continue to unfold and take on more meaning with each repetition. The book and album are companions, woven together: they complement one another, making each other a deeper and richer experience.

Dao Strom: Thank you for these observations, Brian, you are such a generous and attentive listener/reader, the best kind a project like this could hope for, especially in a world that often doesn’t have time for close listening or close looking. I can feel in your work, too, the way that slowing down and allowing things to unfold brings other degrees of attention to greater amplification; which as an act of perceiving can extend beyond the realm of art, too, I think, in beneficial ways.

In making these multimodal hybrid projects, I think I always had in mind they would or should have multiple entry points, or should allow for that possibility at least, and that maybe this is something integral to the hybrid ethos–that structure is fluid. And that experience of the work can be, too. It can be fragmented, it can be nonlinear, it can be just poetry or just music, or it can be a multidimensional kind of “reading”. I guess my impulse is to leave open how a reader or listener will choose to navigate the work, with also the hope that it might shake up how a reader or listener approaches a page, or a song, or language and listening. And I love that your experience has been to find “intimacy and quietness” in the work, as these are definitely qualities of voice I feel drawn to.

I think, in similar though different ways, both of our art/music practices are rooted, as you put it, in a kind of attention to “paying attention”—which seems both very simple and very crucial. It takes effort to listen and there are a lot of layers to hearing.

WOSU: Columbus Composer Brian Harnetty Accompanies the Wisdom of Thomas Merton

The Dalai Lama listed Thomas Merton among the three most influential people in his life. Pope Francis said he “opened new horizons for souls and for the Church.” He was the subject of a Judy Collins song and a play by Charles L. Mee. His writings inspired many, but few have heard him speak. That's one reason it's so compelling to hear Merton's voice accompanied by the music of Columbus composer Brian Harnetty on his 2022 album Words and Silences.

Merton made the recordings in a small hermitage in the hills of Kentucky in 1967. As a Trappist monk, spiritual writer, and social activist, he had a lot to say, and his recordings inspired Brian Harnetty to create a musical accompaniment that adds much to the words of a man who changed countless lives.

Nick Booker recently met with Harnetty and local photographer Linda McDonald at Scioto Audubon Metro Park to talk about the album in the environment Thomas Merton loved best, out among the inspiring beauty of the natural world. Merton had a unique ability to relate abstract philosophical ideas to everyday sights and sounds, and Harnetty seems uniquely able to relate that work to the present moment. During the course of the walk, he pointed out birds, trees, and flowers that Merton would have liked and described “doing the old Merton thing;” using everyday listening practices to understand the deepest qualities of spirituality, humanity, and the universe we inhabit…

— Nick Booker

There Stands the Glass

In recent months the ways in which my approach to life changed during the pandemic have begun to come into focus. Trying to make sense of the days remaining to me as I attempt to develop a better understanding of God outweighs other obligations that once seemed so important.

Encountering The Seven Story Mountain in 2021 played a role in changing my priorities. Thomas Merton’s autobiographical account of his dramatic spiritual transformation inspired me.

Naturally, I was drawn to Words and Silences, an unusual new project overseen by Ohio composer Brian Harnetty. While living on the grounds of the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Kentucky in 1967, Merton recorded his musings on topics including God, philosophy, music and current events. Here’s a visual representation of the opening track “Sound of an Unperplexed Wren.”

Harnetty sets snippets of Merton’s spoken meditations to wistful chamber music. I initially thought Harnetty’s accompaniment was too genteel. I’ve since come to believe the fragile sounds perfectly reflect the ineluctable sadness of mortality voiced by Merton.

Not all of Words and Silences is heavy. Merton documents a “New Year's Eve party of one” as he spins records by jazz artists including Mary Lou Williams. His humanity- as well as Harnetty’s sympathetic enhancements- gives me courage. At one point Merton wonders “who am I who sit here? It’s very difficult to say.” Amen, brother.

Blow Up (Italy)

In the four works that preceded this latest album, Brian Harnetty drew inspiration from the scenes of the Appalachian Mountains in Ohio, where his American ancestors originated. He ideally returned there with a series of compositions which, on the one hand tell how the culture and morphology of those territories have changed, and on the other they appear as an introspective analysis of his own identity. In in "Words and Silences," the same mixture of chamber writing for acoustic ensemble and field recordings is applied to the archive of meditations that the Cistercian monk Thomas Merton recorded on cassette in his hermitage in Kentucky, dating back to 1967 and currently archived at Bellarmine University in Louisville. Philosophical reflections ranging from Sufi mysticism to Samuel Beckett, from reading Foucault to the protest marches of the late sixties, are evoked from the past through the powerful medium of music intelligently harmonized with the flow of words.

Elsewhere (New Zealand)

Another album at Elsewhere which we freely concede will not be for everyone.

But if you've ever heard those whimsically philosophical/Zen readings by John Cage, have enjoyed solo piano, ambient music, bird song and/or spoken word readings, then this thoughtful 49-year old American interdisciplinary writer/researcher/musician and sound artist might just have considerable appeal.

Here Harnetty explores writings and readings by the Cistercian monk and writer Thomas Merton (1915-68) through Merton's own sound archive and journals, with Harnetty's brass and wind group provide elegantly poised settings for the readings. …

Yes, not for everyone but in this world of haste – especially in these harassing times in the lead-up to the shopping frenzy that is Christmas (too much religion, not enough commercialisation for you?).

But maybe this is the reflective wind-down for late evening listening when you can take time to think about your values and the demands the 21st century places on you and yours?

Take the pause this offers. …

Independent Clauses: “An amazing, challenging, intriguing composition”

Harnetty’s vision here is immense: combining the thoughts of a spiritual giant like Merton with compositions that support and showcase the ideas while balancing complex sonic artifacts is a ton to wrap one’s head around. And yet, Harnetty achieves all of that, and the collection here soars. The work is distinctive, immersive, and poignant. It’s an unalloyed triumph and a magnificent achievement. Highly recommended.

Screen of Distance

One of the brightest lights of Columbus composers, Harnetty has done some of his best work interacting with archives. I was sorry Anne and I were out of town for the live debut of this work. His new one, Words and Silences, takes on the American monk and scholar Thomas Merton, using recordings of his own voice. Not “takes on” in terms of grappling with but trying to understand, trying to see Merton as he is and as he presented himself. The arrangements around the vocals often have a cycling, hypnotic feeling, not getting lost in the details but letting them shine just like the diary entries, but those details are all massively important; the clarinet on this track breaks my heart open to let the light in. It’s the best, most fully realized work yet from someone I don’t think has ever made a bad record.

Various Small Flames

A portrait of the Cisteritan monk and writer Thomas Merton, Words and Silences sees Brian Harnetty add original musical compositions to recordings made by Merton himself during his hermitage in Kentucky in 1967. We hear him identify birdsong, listen to gunfire from Fort Knox, celebrate New Year’s Eve alone and comment on an array of topics from Sufi mysticism to Michel Foucault. But more than offering an extraordinary window into Merton’s solitude, the album elucidates the beauty and melancholy inherent within his reflections, honing the endearing doubt which permeates each monologue and furthering the strange contradictions at work. A communication to no-one, immediate in tone but of course now distant too, and very much aware of the artifice of the recording process. Brian Harnetty embraces such conflicts much as Merton did, and thus not only continues the conversation but opens it wider. Words and Silences is a meditation on curiosity, and one which understands uncertainty and inconsistency to be the very foundations of any will to learn.

Salt Peanuts

American, Ohio-based multidisciplinary experimental composer-sound artist-pianist Brian Harnetty is also a sonic archivist, sonic ethnographer, photographer, writer, installation artist, community organizer, environmental activist, and myth-maker, who employs archives, field recordings, turntables, tape machines, radios, orchestras, toy and junk instruments, and his own ensemble for his work. He brings together in-depth ethnographic research and community outreach, over long stretches of time, with the ghosts of sampled archives and his own mix of experimental, ambient, electronic, and folk music. In his works, past and present bleed into one another to spark new music, and imagine new futures. He worked before with the Sun Ra and El Saturn archives in Chicago, and sound archives from rural Kentucky…

…Words and Silences embraces all contradictions in Merton’s thoughts – between voice and silence, past and present, inward and outward, living and dead, time and space, everything and nothing. Harnetty advises us that we may adopt Merton’s sense of openness and playfulness, move between contradicting thoughts, hold them together, and listen as they melt into each other. It is an insightful and heartfelt homage to an inspiring mystic.