“Many are the artists who have been deeply affected by hearing scratchy old recordings, but Brian Harnetty has devised a way to let us simultaneously experience ancient audio documents and his music inspired by them….Harnetty lets us eavesdrop on moments of great beauty….there are so many striking moments…”

“It’s nothing new to create experimental collage out of old records/sound sources, but it’s pretty damn cool to have done it while maintaining an historical archival sense to it all like it’s done here. Great stuff.”

“Brian Harnetty is like a modern version of Alan Lomax, though he is not content to just catalog and present ancient American music. Instead he’s chosen to interact with it by creating collages, contemporary compositions and new ways for archival music to breathe again.”

“Layers of folk songs, news clips and interviews, primarily from the 1950s through 1970s—over a collage of bells, pianos, organs and strings—capture the sadness, texture and beauty of winter, and the underlying hope that can be found in a dark period of transition. At the same time, the essence of the source material isn’t tarnished.”

“Brilliant, maddening, addictive....Harnetty has proved that one way to preserve history is to weave it into the moment and let it vanish in our midst while echoing forever its truths, aphorisms, superstitions, and lies. Highly recommended. 4.5/5 stars.”

“American Winter is a painstakingly compiled collage of overlapping samples augmented by modern instrumentation and post-modern aesthetics. The listening experience is elegiac, beautiful, and utterly unique; with a completely original mix of sounds as old as the hills, undiscovered shards of Americana, and meditative modern drones and shimmers.”

“ In releasing the sadness of these lost voices [Harnetty] does for American folk music what W.G. Sebald did for the European novel.”

“….rather than sculpting songs out of the antiquated material, Harnetty chooses to fashion the recordings into a delicate fabric of forgotten atmospheres, embracing all the nostalgia and feelings of loss therein.”

“A pretty seamless exploration of some deep vaults while recontextualizing the sound of America’s past for a whole new generation.”

“A soft focus gauzy collage pieced together from fragments of Appalachian music and field recordings. Darkly lovely....The audio collages slowly drift in and out of focus, and the results are both engaging in the documentary sense and hauntingly spectral. Recommended!”

“There is something almost uncanny about the way [Harnetty is] able to place his own interventions in relation to the archive material, sometimes appearing not merely to respond to but slightly to anticipate the movements and nuances of their vocals, which creates a most curious simulacrum of liveness....it also creates something not merely poignant but also celebratory, and something respectful but lively and, in the best sense, playful.”

The Wire: "So many striking moments"

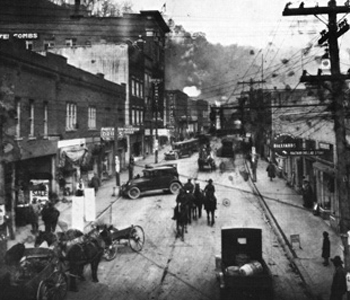

Many are the artists who have been deeply affected by hearing scratchy old recordings, but Brian Harnetty has devised a way to let us simultaneously experience ancient audio documents and his music inspired by them. Harnetty has raided the sound archive at Berea College, Kentucky – a vast collection of 75 years of Appalachian history and culture. Cracked voices recalling almost forgotten songs jostle for space with leisurely yarn-spinners and radio announcers thanking sponsors. Harnetty lets us eavesdrop on moments of great beauty after a song is finished, when the singer is audibly moved, or else wondering why she can’t recall the next verse. One old-timer recounts a 1928 funeral, a vanished world where the crowd stood listening to the preacher and the pelting rain made no difference.

Harnetty’s ‘accompaniments’ to this fascinating material are robust – no clouds of electronica here. He summons textures and patterns from prepared piano, dulcimer, banjo, and junkshop percussion, bright acoustic sounds with plenty of Appalachian links, that entwine marvelously well with the husky voices and shellac crackle. “Drunkard’s Dream” is a perfect match between the old-timey vocal and Harnetty’s clanking gamelan of sounds, as is the snail-paced piano on “While Pacing a Garden”. Elsewhere an anthemic dirge sits astride a driving piano. Harnetty proposes not Ambient background but cohabitating musics. He exposes the gulf between well-fed radio voices and the poor farmers listening in, and makes us aware of the awkwardness of audio documentation: asking an elderly woman to perform a song from her childhood can unblock emotions in an unpredictable way. There are so many striking moments during this album, which Harnetty has dedicated to his former teacher at London’s Royal Academy, Michael Finnissy.

––Clive Bell

Allmusic: 4.5/5 stars, "Brilliant, maddening, addictive"

Chicago's Atavistic Records is well-known for its Unheard Music Series coordinated by John Corbett, as well as being the label of the Vandermark 5, the wild Out Trios series, and other bits of necessary forward-thinking musical ephemera from past and present. It is not, however, recognized for issuing field recordings of all-but-unknown American culture. Brian Harnetty, a Fellow of the Berea College Sound Archives in Kentucky, has assembled one of the most obsessive collections of field recordings from the Appalachian region from that very place, weaving them into what amounts to a 17-"movement" composition that is steeped in ghost trickery. This massive sound archive was the source, along with the help and permission of some of the original song, radio commercial, and dialogue collectors who contribute to both the library and this offering. Don't look for Alan Lomax-type songs and stories here. That's not at all what this is about; in fact, listening to this sounds like eavesdropping on an alien planet. What begins with an old woman trying to remember the old folk song "The Night Is Quite Advancing" becomes a brief radio commercial and then morphs into essentially the same song with different words in "I'll Cross the Briny Ocean." Along the way, Harnetty and his sonic co-conspirators add some double-tracking to twin the piano or a guitar phrase, spoken stories and allegories emerge only to dissolve into a duet of older women singing a folk song that is accompanied by someone from another of these field recordings playing a strange, jumpy, nearly ragtime song on an out-of-tune piano, and the story continues. On and on it goes for 48 minutes and change, never repeating, always moving, yet always standing stock-still. Songs and stories often intertwine, creating a much larger allegory from the ether -- as in the case of "I'll Have to Go Off and Be Gone Tonight," where a toy piano and a pair of women singing about running away and eloping are juxtaposed against and then placed on top of an old man relating a story of a man who murdered his wife after a bad dream.

Brief interludes, like a yodeling radio duet of "Last Night as I Lay on the Prairie," slip into more commercials and public service announcements and reportage of a conscription lottery, slipping in and out of a piano playing some primitive melody on its lower keys, interspersed by disembodied fragments of sung voices and bells, crowd sounds, and an announcement for a draft lottery introduction by the President that never comes. "That Drunkard's Dream" and more toy pianos are punctuated by a single looped banjo, and by ten or 12 minutes in you are gone, off into some world you may be unfamiliar with except as the stuff of legend, and yet are drawn to compulsively. Field hollers, gospel songs, and American farmers prattling -- it all becomes part of an aural tapestry that speaks louder than all the officially released Lomax documents for having been woven into a fabric rather than categorized and separated by date, time, place, person, and what is happening exactly. It just is. It was, but it is, here, now, yet forever out of time and place. Guaranteed to piss off most stuffy "folk music" purists, this is the ultimate folk music, as it borrows from sources it may know or may not but is not divulging except to present them as a living document. The gospel songs in "Soon We'll Reach the Starry Sky" sound like they were recorded by two or three different original sources all spliced together with odd elements like a droning accordion key (or perhaps it's a harmonium), bells, and more; finally, a man who sounds so old he could have been Methuselah is in dialogue with some broke store patrons, saying "We'll look for ya if we come back..." with the great American huckster's truth actually spoken as sincere surprise -- in an exclamation of shock and bitter truth that brings the entire thing back to its beginning and raises the questions of who, what, where, how, and when all over again (but in vain, because this is secret history meant to be offered so as to create a greater secret by its revelation).

And seemingly, just as you are about to enter another rabbit hole of curiosity and entranced, rapt attention: silence. In it you can realize how that last line (which won't be given away here) folds not only the recording, but all of that history, back in on itself all the way back to its lips, into the throat and belly trying to come back out until it disappears into its own mouth, hidden, obfuscated, but ever present resonating in the empty spaces and open-air echoing in the space of moments, decades, centuries. This is a new kind of transmission, one that begs far more questions that it could -- or even want to -- answer, keeping these names and faces eternal yet as anonymous as the land they were swallowed into by the grave. Brilliant, maddening, addictive: this is the kind of stuff Nurse with Wound's Stephen Stapleton lived for back when he was creating his big obscure music list -- and he should add this -- and other sound hunters would give anything to have created. That it was sanctioned by the Berea College Sound Archives is even more remarkable. Harnetty has proved that one way to preserve history is to weave it into the moment and let it vanish in our midst while echoing forever its truths, aphorisms, superstitions, and lies. Highly recommended.

––Thom Jurek

Other Music: Featured New Release, "delicate fabric of forgotten atmospheres"

Brian Harnetty's American Winter is an intricately woven album of collaged archival recordings from the Appalachian collections at Berea College in Kentucky. Field recordings, radio programs, advertisements and interviews from the last 75 years commingle in a strange atmosphere that is not quite timeless, but perhaps could be described as "a-temporal". Yet while Harnetty's source material is clearly old -- much of it sounding like it was taken from old analog tapes, recorded wires, and 78s -- the compositional sensibility at work here is unmistakably current. The crackle and hiss of the old recordings -- from sources as diverse as national news broadcasts and intimate home recordings -- runs parallel with the crystal clarity of what sound like more recently recorded textures of accordions, pianos, banjos, bells, and electronic sounds from Harnetty's laptop. I couldn't help but be reminded of the similarly Appalachian influenced collage work of the Books when listening to this record, but rather than sculpting songs out of the antiquated material, Harnetty chooses to fashion the recordings into a delicate fabric of forgotten atmospheres, embracing all the nostalgia and feelings of loss therein.

––Che Chen

Vital Weekly, influential weekly from the Netherlands: "very odd but great"

If there was a serious question mark corner in Vital Weekly, then the CD by Brian Harnetty would be taken poll position there. Harnetty is a college professor in Kenyon. The music he presents here uses sounds from The Berea College (Kentucky) Sound Archives which 'hold non commercial recordings documenting more than 75 years of Appalachian history and culture'. Harnetty takes these audio documents consisting mainly of people talking and singing and may or not set music to that. May, as sometimes I think he does when he adds piano or guitar or layers them, adds some echo, and sometimes it seems as pure and clean as possible. This leads to a fascinating audio document which holds somewhere in between a radioplay, a documentary, a work of music and a field recording. I couldn't help thinking of the work of Dominique Petitgand. The way the voices are mixed with sparse music, the intimacy of it all, it all sounded like a US version of Petitgand. Very odd but great CD.

––Frans de Waard

Aquarius Records, San Francisco: "darkly lovely....hauntingly spectral"

A soft focus gauzy collage pieced together from fragments of Appalachian music and field recordings. Darkly lovely. Darkly resonant and fascinating. The seventeen tracks of Brian Harnetty's American Winter album are like the slowly disintegrating pages of a stranger's scrapbook. Harnetty artfully and respectfully pieced together segments of dialogue, field recordings and radio transmissions among other things which he drew from the vast audio archives of Berea College where he is a member of the Appalachian Music Fellowship Program. Highlights such as "I'll Have To Go Off And Be Gone Tonight" feature fragments of oral histories from Appalachian folks accompanied by the gentle wheeze of what sounds like an accordion and the tinkling of a toy piano. The audio collages slowly drift in and out of focus, and the results are both engaging in the documentary sense and hauntingly spectral. Recommended!

Dusted Magazine: "recontextualizing the sound of America’s past for a whole new generation"

Ever since a little bald vegan ruined it for all of humanity, I generally can’t get into people messing with quality field recordings and archival sounds. Harnetty redeems that whole idea, though, presenting a pretty seamless exploration of some deep vaults while recontextualizing the sound of America’s past for a whole new generation.

––Michael Crumsho

Columbus Alive: "hearing a relative's ghost"

A sample-based producer's main obstacle is usually copyright infringement. On his latest record, that wasn't an issue for Columbus-based composer Brian Harnetty, an OSU grad with a master's from London's Royal Academy of Music. When he began work on American Winter, out on respected experimental imprint Atavistic and celebrated with a release party Friday at Andyman's Treehous, he had full permission to use his source material. Berea College in Kentucky was actually paying him on fellowship to dig through their catalog. And just as Madlib's access to the Blue Note catalog for his Shades of Blue album was a goldmine for a jazz fiend, Harnetty was very pleased with the folk collection he rummaged through. "The [Berea] sound archives, as far as Appalachian music, is second only to the Smithsonian," he said. "It's really impressive and they are very knowledgeable about the tradition of music."

With sampling restrictions out of the way, Harnetty's challenge was to create new art without disrespecting the historical and personal value of the music. "My approach was kind of like an outsider," he explained. "I was trying to find the balance to using it as material and also respecting the people that made the music. Beforehand, I was doing stuff with samples—old turntables, using material to just layer on top of one another. But when I got down there, I was meeting the relatives of the people that were on the recordings, and I got freaked out."

Harnetty's initial involvement with Berea stemmed from his membership in the art collective Fossil Fools, which did a project paralleling war in oil-rich Iraq and coal mining in Kentucky, comparing the effects on soldiers and miners in pursuit of energy. It hooked him up with Appalshop, an Appalachian arts and education center, which led to his contacts at the college.

From a listen to American Winter, I think Harnetty can put his concerns about exploiting Berea's resources to rest. He nails his chosen themes of war, travel and winter. Layers of folk songs, news clips and interviews, primarily from the 1950s through 1970s—over a collage of bells, pianos, organs and strings—capture the sadness, texture and beauty of winter, and the underlying hope that can be found in a dark period of transition. At the same time, the essence of the source material isn't tarnished. Harnetty's also gotten a positive review from one of his most feared critics. After presenting parts of his composition to relatives of people whose lives were on the sound clips, one family member described it as hearing a relative's ghost.

––Wesley Flexner

KZSU, Stanford: "great stuff"

Archival recordings of Appalachian folk singers/radio broadcasts, with studio banter/outtakes, etc placed over soundbeds of piano, sometimes minimal, always dissonant. This mix is sorta obviously juxtaposed, but the recordings might not be listenable otherwise, relegated to novelty/historical archives. The sound beds are quite interesting and cool, experimental at times but mostly appropriate feeling banjo, out of tune piano, traditional instruments, feel. Its nothing new to create experimental collage out of old records/sound sources, but its pretty damn cool to have done it while maintaining an historical archival sense to it all like its done here. Great stuff:

1) old timey singer in the studio sings simple folk song, captured with banter, with sound bed of eno’esque sparse piano

2) 17 second radio promo/commercial

3) nearly creepy female vocals made creepier with piano and electronic soundbed

4) story telling by an old man layered with a capela folk song and player piano

5) radio excerpt of lovely 1940’s yodel style western, female duet, unfortunately brief, cut-off

6) radio news reports over soundbed of piano playing, introduces the president but he never appears, a perfect intro to a next song with Duh-bya or the like

7) woman singing simple folk song over toy pianos

8) brief harmonium and fiddle 9) similar to #3 but piano never turns electronic

10) recording of funeral story from 1928, over toy piano, electronic washes

11) radio sample intro, then banjo playing soundbed with field recordings of conversations with old timers and old woman singing minor toned folk song

12) snippets of radio program, farming subjects, with piano

13) very brief, Arthur Godfrey on the radio, “praise the lord and pass the ammunition”

14) doubled piano playing and dulcimer provides cool soundbed to more folk songs

15) wartime radio broadcast to start, then old woman telling stories, singing over harmonium and toy piano

16) minimal music with female and male folk singing juxtaposed

17) brief recording of toothless old man you cant hardly understand, weird

––Your Imaginary Friend, KZSU, Stanford

Thompson's Bank, London, UK: "poignant, celebratory, respectful, lively, playful"

Well, here’s a treat: but you need to know the backstory. There is a large sound archive at Berea College in Kentucky which documents Appalachian music and culture; the musician and sound artist Brian Harnetty was invited to explore and work with these recordings, and the utterly captivating American Winter is the result. Essentially Harnetty has chosen a number of extracts (mostly unaccompanied songs, though he is careful to leave in accompanying bits of chat; but also stories and bits of radio broadcasts), and overlaid them with music of his own: piano (with particularly effective use of thumbtack and toy pianos), banjo, percussion and so on. If what I’m describing sounds like highbrow Moby, banish such thoughts now: Harnetty has worked with immense sensitivity to his sources and managed to create what feels like a genuine dialogue with them. Quite often he simply creates an accompaniment for the a capella singer: but there is something almost uncanny about the way he’s able to place his own interventions in relation to the archive material, sometimes appearing not merely to respond to but slightly to anticipate the movements and nuances of their vocals, which creates a most curious simulacrum of liveness. This album is up with the uses of taped sources in Gavin Bryars’s "Jesus Blood Never Failed Me Yet" and John Adams’s "Christian Zeal and Activity" for emotional depth and affect, but like both of those it also creates something not merely poignant but also celebratory, and something respectful but lively and, in the best sense, playful. I’m so pleased to have come across American Winter and, through it, the work of an obviously immensely gifted artist.

––Chris Goode

End of An Ear Records, Austin, Texas: "the original Jandek, seriously"?!

The original Jandek, seriously. This is some crazy hermetic folk / sound art songs with home ambiences and backwards pianos and other unexpected weirdness. Awesome!

Songs Illinois: "new ways for archival music to breathe again"

Brian Harnetty is like a modern version of Alan Lomax, though he is not content to just catalog and present ancient American music. Instead he’s chosen to interact with it by creating collages, contemporary compositions and new ways for archival music to breathe again. To do this he gained access to the extensive sound archives of Berea College (Kentucky). These archives collect more than 75 years of Appalachian history in the form of music, field recordings, oral histories and radio programs. He added live instrumentation to the field recordings and pieced various audio discoveries together to form a whole cohesive work that addresses as he states: “The pieces point toward both the season of winter and to more ambiguous ideas: the winter of politics, war, emotion, history, and finally to its ultimate hope of renewal.” The great Chicago based experimental label Atavistic Records will release American Winter.

Deep Discount: "elegiac, beautiful, and utterly unique"

In 2005, Brian Harnetty became one of the first Appalachian Music Fellows trained by the Berea College Appalachian Music Fellowship Program to gain access to the college's enormous archives. AMERICAN WINTER is a painstakingly compiled collage of overlapping samples augmented by modern instrumentation and post-modern aesthetics. The listening experience is elegiac, beautiful, and utterly unique; with a completely original mix of sounds as old as the hills, undiscovered shards of Americana, and meditative modern drones and shimmers. Perfect for fans of adventurous folk music, serious experimentalism, and aural pastiche.

S.S. Smith, Amazon:

The fruits of Harnetty's academic access to field recordings from the Berea College Sound Archives in Kentucky are treated with hypnotic accompaniments from piano, banjo and what sounds like a dulcimer. The snap, crackle and pop of the original recordings is also given the special resonance of an instrumental accompaniment. Some treatments have a minimalist John Adams quality with the ghost of Nancarrow's player-piano in them too. Other sparser arrangements appear to haunt the originals with Cage-like suspensions and modified instrumentation. Harnetty's treatments are never embellishments - the original material is treated as part of the ensemble. The shock of this music - often evident in interruptions and interjections by the original singers and recording engineers - is its humanity. Though this is often foregrounded by the orchestration that Harnetty has imposed, it is never mawkish. In fact, it reveals itself only slowly and builds a cumulative power over the whole recording. It is the sound of something windblown caught up in telegraph wires. In releasing the sadness of these lost voices he does for American folk music what W.G. Sebald did for the European novel.