“Harnetty’s music is equally calm and nuanced and wise in its response, as practiced as its models, which include not only these voices but also the fiddle music that cranks up in occasions for performance so very long ago and once upon a time but present for us again here.”

“Dense, rich, haunting and evocative... take your time and savour the material; it’s a slow burn and all the better for it... out of the mouths of children come unlooked-for truths and myths and Mr. Harnetty has stitched them together into a forceful narrative that delights and shocks.”

“Both eerie and compelling.”

“There’s a very effective haloing of the voices by the music that provides a layer of remove, reminding us that these are “ghost stories” in many senses of the word.”

“ ...A kind of spectral music box jazz-for-voices, imbued with a deep eerie poignancy. 4 stars.”

“Spliced and meshed with instrumentation both old and newly composed, these stories are revived as haunting tone-poems, enigmatic time-capsules that swirl about in a tintype haze.”

“This is a dialogue between past and present, memory and action, grisly, strange, and compelling.”

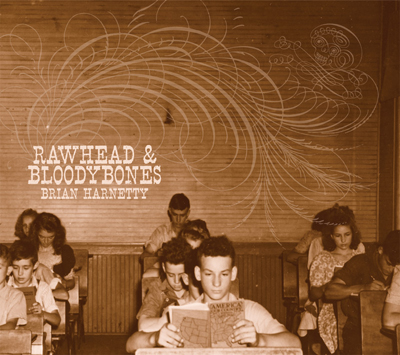

Album Liner Notes:

Seven miles north of Hyden, Kentucky there’s a town called Dryhill. Locals know it also as Hell for Certain, or Hell-fer-Sartin, as you’ll find it spelled in South from Hell-fer-Sartin: Kentucky Mountain Folk Tales, the best-known book by folklorist Leonard Ward Roberts. The folk tales that Brian Harnetty samples in Rawhead and Bloodybones can be found there. Roberts collected his tales “on the north side of the Pine Mountain range,” driving from town to town in his jeep, fearing already in the late 1940s and early 1950s that the way of life keeping these old stories alive was about to disappear: “I had little difficulty in finding an electrical outlet for my tape recorder.” Roberts went to schools to record “informants,” as he calls them. At the school in Hyden, he found Jane Muncy, aged 11, who’d heard “Merrywise” from the grandmother raising her, and Janis Moran, 12, who tells “Jack and His Master” for us here seventy years later.

In the back of his book Roberts lists parallel stories and versions for the tales and catalogs their motifs, following the Aarne-Thompson classification system. The source texts are mostly English and Anglo-Celtic, with splashes of German and French. Grimm and Perrault are regularly cited. Scholars will want to know these things, but it is the idioms and rhythms and timbre of the telling, the encounter between language and voice that Roland Barthes famously described as “the grain of the voice” that must have mattered most to Harnetty as he embraced these tales. Repetition and symmetries ease their telling, as with all oral traditions, and the music recognizes this: if it’s gold combed out of the good girl’s hair it’s snakes and frogs falling from the bad girl’s. Then there are the journeys with much to endure—hiding from Jack and His Master in a blood-hole, only to have the severed ring finger from an old woman they’ve captured land in your lap. Or you are lowering your bucket in the well and fish up skulls that want to chant for you: “Wash me dry me lay me down.” Nobody is the least bit perturbed by these gruesome happenings, least of all the narrators who rattle off the tales with such precocious professionalism. Jane and Janis are obviously delighted to be performing for their audience, for the tape recorder of Roberts. Their tales tell us that human butchery and sudden death exist side by side with goodness and luck, and they celebrate the resourcefulness and courage that used to be called pluck: “I told you to get out of my water bucket and hush” one heroine says to a chattering skull. Harnetty’s music is equally calm and nuanced and wise in its response, as practiced as its models, which include not only these voices but also the fiddle music that cranks up in occasions for performance so very long ago and once upon a time but present for us again here.

–– Keith Tuma, 2015

MOJO Magazine: 4 stars:

For nearly 10 years Ohio sound artist Brian Harnetty has been immersed in Kentucky's Berea College Appalachian Sound Archives, composing new arrangements for found songs and voices. Here he rescores eight gruesome children's tales of witches, bears, and serial killers into a kind of spectral music box jazz-for-voices, imbued with a deep eerie poignancy. 4 stars.

–– Andrew Male, April, 2016

Ethnomusicology Forum:

While the vast majority of Dust to Digital’s releases are historical recordings, in a few instances the label has released more contemporary work. … 2015’s Rawhead & Bloodybones by Brian Harnetty consists of archival Appalachian field recordings arranged and contextualized by new material composed by Harnetty. Harnetty calls the resulting work ‘sound-collages’ and over the years he has worked with archives such as the Berea College Appalachian Sound Archives in Kentucky, and the Sun Ra/El Saturn Collection at the Creative Audio Archive in Chicago. Rawhead & Bloodybones references a legendary bogeyman figure(s) popular in the folklore of the American South and places samples from 1940s field recordings of these often gruesome tales – here told primarily by children – against Harnetty’s newly composed instrumental accompaniment. The result is both eerie and compelling. … Read the article here.

— Dr. Marian Jago, 2021

The Operative Magazine:

Dust-to-Digital, the Atlanta-based imprint responsible for some of 2015′s most sterling collections of scavenged and crate-dug archival recordings, has capped off a landmark year with Rawhead & Bloodybones, a new album by composer Brian Harnetty. Harnetty’s pairing with Dust-, a label with firm stakes in the business of storytelling and cultural resurrection, couldn’t be more apt; toeing the ever-eroding line between musical composition and sound art, Harnetty specializes in a brand of sonic collage that weaves rich narrative patchworks from dense and disparate source material. If he was last seen culling from the Sun Ra/El Saturn collection on The Star-Faced One (2013), a constellatory portrait of the late, great Ra, Harnetty’s now grounded himself firmly in Appalachia with Rawhead, a cross-sectional window into American folklore.

Through collaboration with the Berea College Appalachian Sound Archives in Kentucky, Harnetty has compiled recordings that find a series of speakers delivering tales of the quotidian, wondrous, and (more often than not) deeply macabre. Spliced and meshed with instrumentation both old and newly composed, these stories are revived as haunting tone-poems, enigmatic time-capsules that swirl about in a tintype haze. “Merrywise,” recounted by a young girl named Jane Muncy, is the record’s emblematic opening track—one which spins a yarn of a young boy, a witch, and well, I won’t spoil it…

–– December, 2015

The Big City: Personal Best list of 2015

Not the usual archival release from Dust-to-Digital, but new music from composer Harnetty. He combines samples of music and spoken audio from both the Berea College Appalachian Sound Archives and the Sun Ra/El Saturn Creative Audio Archive, and to the prerecorded music he adds original, acoustic touches. This is a dialogue between past and present, memory and action, grisly, strange, and compelling.

––George Grella, Jr., December, 2015

Christian B. Carey:

For label Dust-to-Digital’s fiftieth release, they tap composer Brian Harnetty, an artist known for blending vintage spoken word and field recordings with his own music. Rawhead and Bloody Bones features 1940s accounts by young people of scary stories. The contrast between Harnetty’s music, which references both traditional Appalachian styles and contemporary folktronica, and the recounting of often grisly tales in children’s voices, is at times startling. But there’s a very effective haloing of the voices by the music that provides a layer of remove, reminding us that these are “ghost stories” in many senses of the word.

A second disc of instrumentals brings the essentials of Harnetty’s creations to the surface, consisting of gentle electronics, vibraphone and chimes, solo banjo and viola lines, and sustained chords from saxophone and trumpet. Two very different sides of the same coin, Rawhead and Bloody Bones is the better for the inclusion of both CDs.

–– January, 2016