Photo courtesy of the Ross Art Museum.

OHIO IMPRINT (2023)

In the fall of 2022, I brought videographer Kevin Davison with me throughout central and southern Ohio, re-tracing the footsteps of photographer Dick Arentz (b. 1935). We found the precise locations of seven of Arentz’s photos, in the towns of Mechanicsburg, Delaware, Chillicothe, Jackson, Ripley, Tyndall, and the Serpent Mound in Peebles. In each location, we made field recordings and recorded several minutes of video. The goal was to understand these places in new ways, to see them through Arentz’s eyes, and to experience what was happening beyond the photograph. As the project unfolded, I began to realize that the “imprint” implied in the project’s title is not only the marks made on photosensitive materials or on digital audio and video, but also the impression each place made on me. I was subjectively experiencing each place in context.

The exhibit consists of seven videos (corresponding with the Arentz photographs) and a soundtrack of collaged field recordings made at each location. Below, you’ll find my written impressions of each location, including things seen and heard, as well as people we met along the way. These impressions also offer some historical context to the sites, and search for the stories beyond the image.

Ohio Imprint was commissioned by the Richard M. Ross Museum at Ohio Wesleyan University. It is part of their “Artists in the Archive Series,” where contemporary artists are invited to work with objects from the museum’s collection to make new work.

The exhibition was from January 18 to March 26, 2023.

SEE: EXHIBITION PHOTOS

WATCH: A CONTINUOUS VERSION OF EACH LOCATION

READ: IMPRESSIONS OF EACH SITE

MECHANICSBURG

Warm fall evening, September. Maple Grove Road, just off West Sandusky Street, at the border of town. The field is fallow this year, carpeted over with grass. A grain mill is still in the background (this mill, by the way, stands in the center of town, revealing Mechanicsburg’s ties to local farming). Cars drive past, some fast, some slow, enjoying one of the last warm evenings of the year. I hear: fall field crickets, a dog barking, a far off red-tailed hawk, two birds in the field squawking to one another, a steady stream of cars, a distant plane. We are not quite in someone’s yard. It is the “golden hour,” just before sunset. I imagine what it must be like to live here, walking among the tall grass, ever-present cars, working in the fields, touched by the land.

DELAWARE

Off of South Sandusky Street, between Pumphrey Terrace and English Terrace, and just a few blocks from the museum. I imagine Arentz driving through the streets until something catches his eye. What is it? A historical marker? An unusual dip or valley between two streets? A huge old oak tree? Now, the tree is gone (there is still a shadow of a stump on the ground), falling in a storm several years after Arentz made his photograph here. New trees fill the space.

There are city sounds: motorcycles, the drone of freeways, and the constant hum of birds and crickets and katydids. A family approaches, curious to know what we are doing. Their young children run on the streets and tumble down into the valley. Laughter, playing, conversation. We talk of this place, once known as Camp Delaware, where black (segregated, and down the road) and white soldiers stayed during the Civil War, waiting for their deployment south. Later, I find a stunning photo in the Library of Congress of a young Qualls Tibbs (1836-1922), a black soldier who posed here for an ambrotype photograph in a freshly adorned uniform and holding a musket. I think of him, proudly preparing to fight.

Curiously, this is a place I have been to before. As a child, I visited my brother-in-law’s family on this street, in a house on the corner, where he grew up. My nieces used to play and tumble down the hills, too, repeating the same patterns of life. I imagine all of the people who have stood here, in this valley, of children and soldiers, of native people, and of Dick Arentz, and now finally me, too, listening and watching and contemplating as the place marks me—makes an impression on me—as my own family stands beside me doing the same.

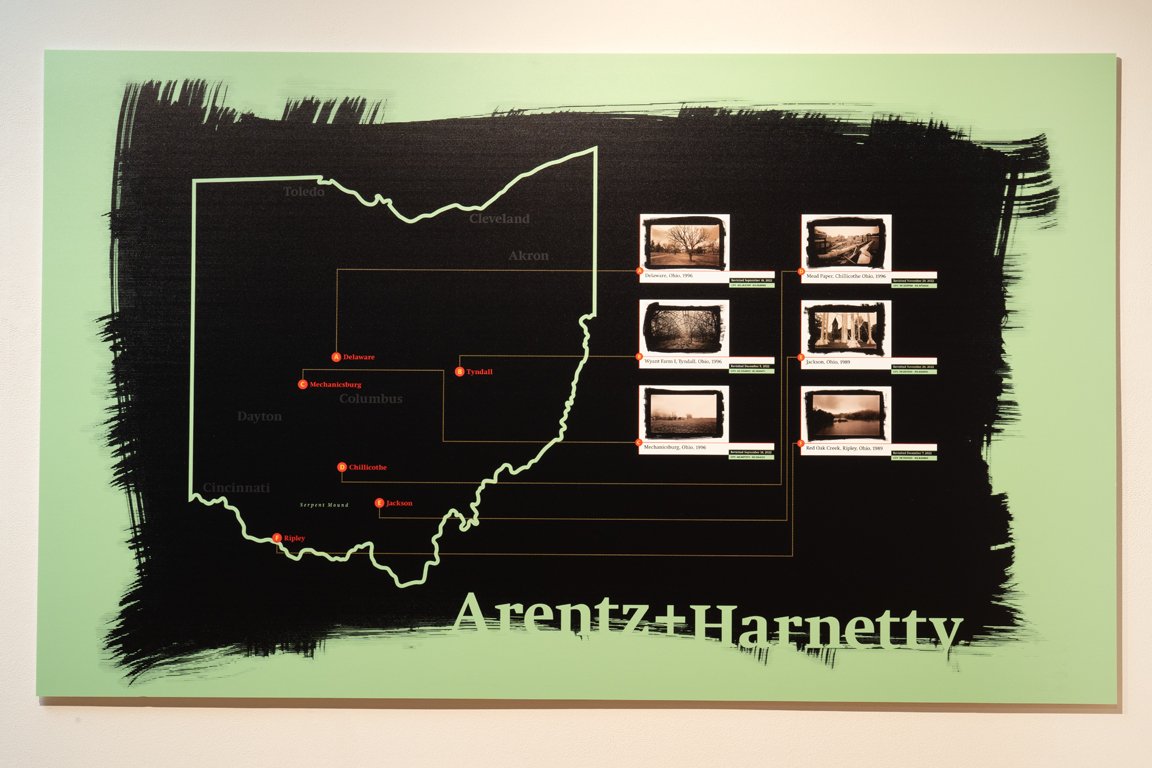

A map of Ohio with locations of each photograph (designed by the Ross Art Museum).

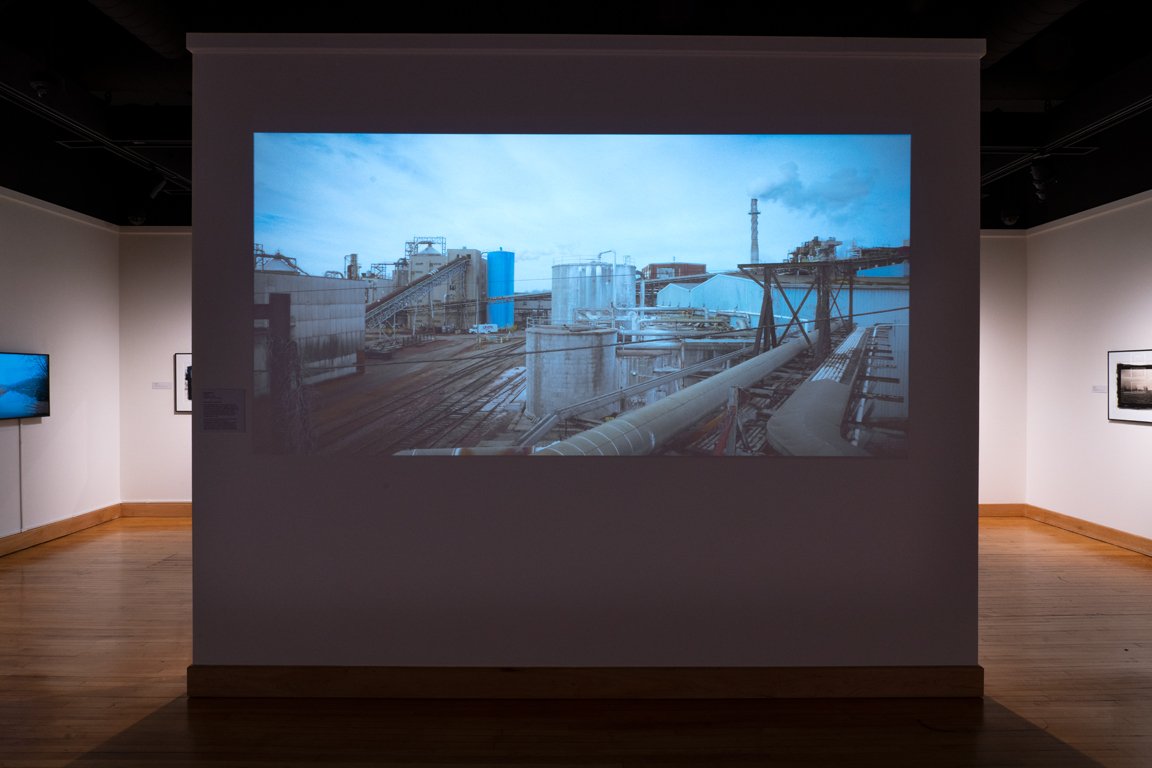

Video still from Ohio Imprint.

Arentz’s original photograph in Chillicothe.

A view of the paper plant in Chillicothe, from Ohio Imprint.

CHILLICOTHE

Kevin and I walk up Bridge Road, carrying equipment onto a narrow strip of the bridge. Is this what Arentz did, too? It is precarious, dangerous. There is no walkway. We find the spot where he took his photograph of the old paper mill, of criss-crossing pipes and elevators, trains and silos full of pulpy chemicals. Cars and trucks fly by, shaking the bridge. We wonder if someone will come out to greet us, and ask us what we are doing. No one does. We watch smoke stacks at full blast, with a group of birds weaving in and out and around the smoke. Trucks and carts move below, full of people working, their hard hats and vests offering small saturated streaks of color. Great piles of shredded trees move along the elevator from across the freeway, up and over and down. And, of course, there is the smell—not too bad at first, but once we are downwind it is acrid and overwhelming—chemicals, wood pulp, wet dog, thick smoke and bitter steam. I still taste it hours later. I ask someone who grew up there how he could stand it, and he replied, “My mom always told me that was the smell of money. As long as the smell was there, we knew we still had jobs.”

JACKSON

The First Presbyterian Church stands in the distance, at the corner of Church Street and Court Street; its architecture and brick facade are modest and elegant. I wonder why Arentz chose to photograph it through the cables and structure of a water tower. The longer I look, however, I see how the tower and church blend together, the angles of wire parallel and also intersecting; they are close, but do not quite line up. I see it differently now: Arentz is showing me the lines, and a new way to read this cityscape. I look up, and see a giant apple painted on top of the tower. Just to the right, there are electrical boxes, new since Arentz’s photograph, steady with the ubiquitous hum of electricity and industry. The picnic table is no longer there. I wonder what it was like to eat lunch in this place.

I listen: noontime bells are first heard at the church, and then again down the street. We are situated off of the main road, behind buildings, full of quiet alleys and half-filled parking lots. I feel the town's energy, languid yet active, where people still care for the buildings and hopefully for each other, too. We meet a man who lives there, gregarious and kind, who shows us photos of past residents who walked the same streets, people who took pride in the town and in themselves. We stop for lunch, and I eat a salad and note the brick walls, old signs, fresh paint, and hope.

Video still from Ohio Imprint.

Arentz’s original photograph of Ripley.

RIPLEY

Looking at the map, I could not figure out where this location was. But we had already visited several sites, and as we put ourselves in the mind of Arentz, we noticed a pattern in his travels: often standing on a bridge; convenient locations to get to (just off main roads); and with a place to park close by. As soon as we arrive in Ripley, we find this spot right away: South 2nd Street, just off of Route 62, near the mouth of Redoak Creek as it dumps into the Ohio River. It is in the shadow of the John Rankin House, and just a few blocks from the John Parker House, two well-known stops on the Underground Railroad, where escaped slaves cross the river on their journey north.

The view—standing on a busy bridge (this time with a walkway, thankfully)—is serene. A vulture flies across the water, then an eagle, then a heron. The sounds are less serene, but still of interest: steady traffic, the rush of cars across the bridge echoing off of the water below, and occasionally you can hear trucks hitting distant rumble strips or applying their jake brakes.

There is a team of surveyors working below. They silently nod to us, unconcerned that we are here with all of our equipment. They have a small dinghy, and quietly float across the water. I imagine they are enjoying their time and work. Looking out at the scene, I am not surprised the steamboat is gone (too late in the season, perhaps). And sadly, we just miss the fog (it was thick our entire drive down, and had just burned off). I enjoy seeing the blue docks, however, and the red truck to the left, providing a bit of color on an otherwise muted Ohio day. As we leave, the noon tornado alarm blasts. We drive down the street and eat subs, and then record along the Ohio river as a barge floats quietly into the Redoak Creek.

TYNDALL

Tyndall is a small village off Route 16 on the slope of the Muskingum river, just south of Coshocton. Once we peel off the main road it becomes quiet, suddenly remote. “These are good motorcycle roads,” Kevin comments. Yet, this is the only location where we can not find the subject of Arentz’s photo: an aging, abandoned glass greenhouse, almost certainly now gone. We scour the maps, driving up and down each street several times. I speak to a man repairing his gutters. We inquire at a local convenience store. Kevin even knocks on a few doors, talking with older women won over by his friendly demeanor. But we still can’t find the location. The most likely spot, right along the main road, houses a relatively new barn. But as we approach, it is fiercely guarded by a dog, and we decline to stay. Finally, at dusk, we settle on an empty, flat field, cars in the distance, imagining the greenhouse could have been there decades earlier. It is a beautiful spot, a farm up the way, rows of clouds slipping through the sky.

SERPENT MOUND

When we arrive at the gate for the Serpent Mound in Peebles, the attendant informs us that the lookout tower is closed for the season. I was certain Arentz took his “self-portrait” photo while perched upon this tower, and am disappointed we are not going to be in the same spot. However, as we approach the mound, it becomes clear that Arentz did not climb the tower, but instead stood below, in its shadow. I marvel at how a photo can deceive, and can be perceived so differently than experiencing the actual place. We set up, and are two of only a handful of people visiting the park that day.

This is perhaps the most quiet place we visit: traffic is still constant, but far off. The air is completely still. Crows call to each other in the trees. The site feels profound, and its quiet sounds add to this feeling. As Kevin sets up the shot, I walk around the mound, recording. I meet a woman who kindly asked the question I most often ask others: what do you hear? I hear birds mostly, far-off trucks, the swishing of my own feet, laughter. We also meet a group of three young men who came down from Michigan to visit the mound. One has a baseball hat that says, “You are standing on native land.” I recognize their youthful excitement of being there, and of being on a spontaneous road trip. “Maybe we’ll go visit another effigy mound right after this,” one says to me. Kevin and I finish just as the park closes, and before leaving I notice how this place is positioned up on a hill overlooking broad farm and forest valleys below. I think of the ancient peoples who traveled to this remote place and understood it to be sacred. I turn to listen one last time, straining to hear traces from the past alongside the present moment. Then, we head to the car and drive home.