COULD I TELL YOU A LITTLE STORY ABOUT THAT?

Experimental Music Yearbook, 2015

In December, 2015, I contributed an essay, score, and recording to the Experimental Music Yearbook. Curated by Travis Just that year, the Yearbook acts as "a repository for composers, performers, and the public to glean the methods and styles of various artists working in the experimental music tradition." My essay, Could I Tell You A Little Story About That?, was based on an ethnography of southeastern Appalachian Ohio, and the coal towns my family emigrated to in the nineteenth century. To visit the Experimental Music Yearbook, click here.

The Shawnee High School Orchestra, 1924. My grandfather Mordecai Williams is in the back row, fifth from the left, and his brother Bill is to his left.

Could I Tell You A Little Story About That?

Much like the past, sound does not stay put. Instead, it leaks and flows, emerges and dissipates; it returns and echoes fleetingly. What we are left with––if lucky––are the objects that sound fills, resonates in, and departs from. Sounds from the past are long gone and yet we strain our ears to hear. We hope to catch a moment of them, often to no avail. But there are clues. In February of 2014, I stand in the middle of a partially restored theater in Shawnee, a town in rural southeastern Appalachian Ohio. The theater was at one time called the “Indian,” then the “New Linda,” and now finally the “Tecumseh.” The walls are stripped down to their latticework. The old, faded, and moth-eaten tapestry over the stage is still hanging, and the hall is mostly empty save a few seats and artifacts: shattered records, glass bottles, film fragments, a beat-up piano, a light box that says, “To-night/Basket-Ball/Dancing.”

As I listen, the theater is noticeably quiet. There is wind outside, an occasional car passes by, and creaking sounds descend from the third floor above me. In this place, I also strain to listen to the sounds that occurred here almost exactly eighty-nine years before, on February 28, 1925. The event, titled “Preliminary Triangular Music Contest,” was essentially a battle-of-the-bands between two high school orchestras from Perry County: Junction City versus Shawnee. I imagine the two orchestras sitting across from one another and beginning to tune their instruments. A jumble of violins, saxophones, piano, coronets, trombones, and drums clash. The sounds move down the stairs and out into the cold, as the doors are opened and the audience files into the theater. I listen for laughter, gossiping, feet shuffling, polite clapping. According to the program, there are violin, vocal, and piano solos, as well as numbers with the entire orchestras. After each school plays through eight selections, judges tally scores, and cheers and stomping are heard from the balcony as Shawnee wins, 5-3.

My grandfather, Mordecai Derwood Williams (1907-67), sits in the Shawnee orchestra, next to his brother Bill. They are both playing saxophone. 1925 is Mordecai’s senior year in high school, and playing in the orchestra is just one of many roles he performs in Shawnee. In the same room as the music contest, perhaps even the night before, Mordecai leads the Shawnee basketball team as captain. The 1925 high school yearbook comments, “Mort is a popular Captt. and his team have had confidence in his headwork in the critical places. We are sorry to lose him this year.” Chairs moved aside and hoops installed, the Tecumseh Theater transforms and adapts to the event, and so does Mordecai. I imagine the scene to be raucous, the muffled sounds of feet running and squeaking along with the ball bouncing and crowd cheering, audible from the floors above and below the theater.

At the end of April of the same year and again in the Tecumseh Theater, Mordecai graduates in a class of 27. The graduation, more formal than the previous two events, has music that includes performances of sentimental and light-orchestral songs, including Percy Granger’s “Country Gardens.” I do not know if Mordecai played with the orchestra or sat with his fellow graduates, although it seems reasonable to imagine that he may have enjoyed performing both roles at once.

These three events––musical contest, basketball game, and graduation––bring together a person and a place over a concentrated period of time. The narrative of my grandfather acts as a framework for emplacing and listening to historical sounds, and I situate myself in the physical space of the theater to listen to the past as it simultaneously reverberates in the present. The experiences of my grandfather at the Tecumseh Theater are a small part of the much larger cluster of historical events of the region. Shawnee is part of a network of coal mining towns, and their history shows an unfolding story of energy booms and busts over the past two centuries. Today, hydraulic fracturing (or, “fracking”) is making its mark as the latest iteration of this destructive pattern, while the town continues to struggle to maintain economic viability.

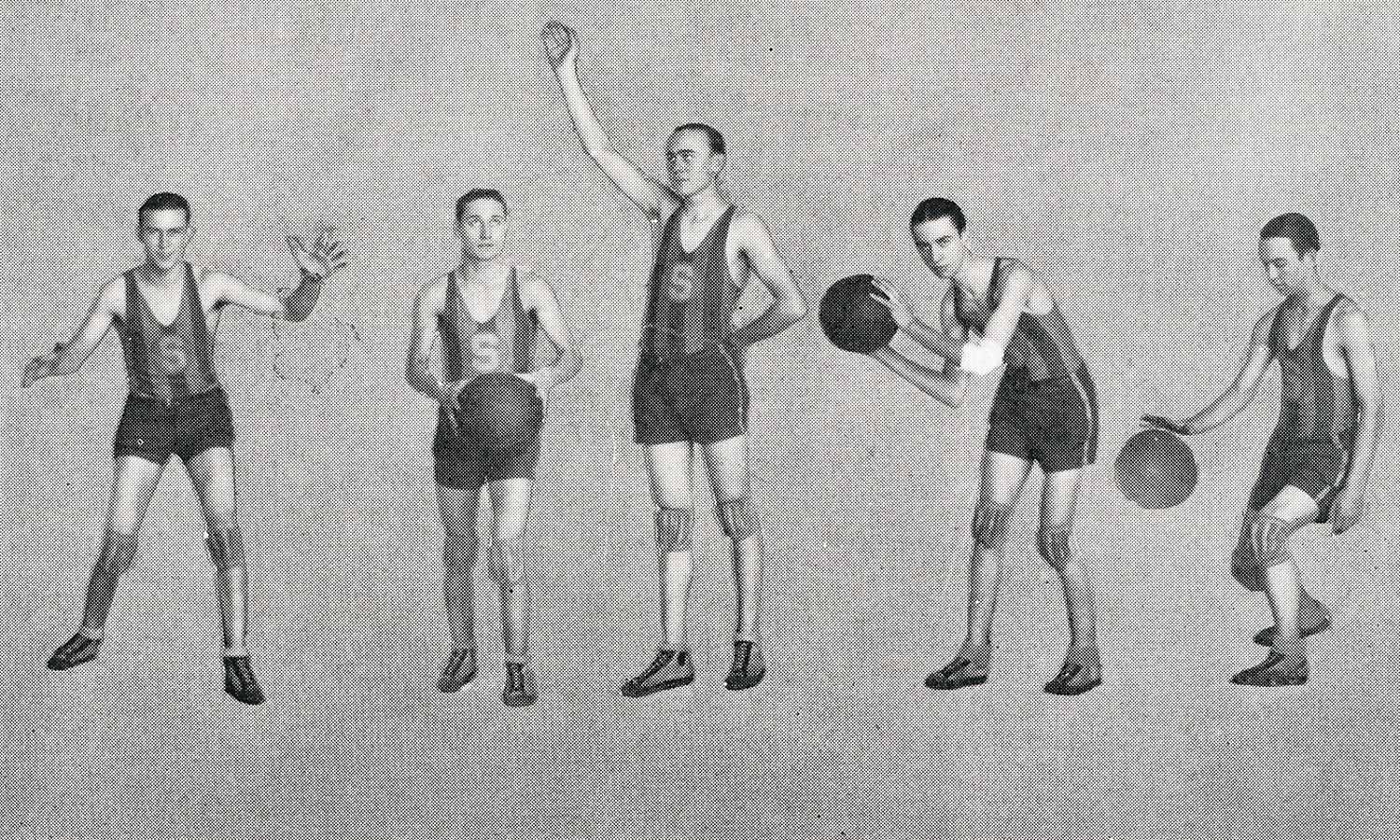

The Shawnee High School basketball team, 1925. My grandfather is second from the right.

All of this brings us to the piece of music offered here for the Experimental Music Yearbook. It is in the same Tecumseh Theater in the 1980s and 90s that several generations of Shawnee residents met regularly to discuss and record their own histories. They spoke of their childhood, town life, and how mining and different forms of extraction affected them. These accounts were kept in storage along with interviews and miscellaneous field and musical recordings. When I inquired about them a few years ago, their caretaker rummaged through a closet and produced a cardboard box filled with cassette tapes already in various stages of deterioration.

While it does not directly draw from my grandfather’s experiences in the theater, Could I tell you a little story about that? samples several of these archival recordings and combines them with vibraphone, performed here by Aaron Michael Butler. The acts of standing in the theater, researching the history of the town and region, listening to these recordings, and imagining the past all inform my composition process. Aural speculation and archival listening come together to create an imaginative space quiet and open enough to allow these different voices to exist together simultaneously.

Still, I am wary of nostalgia. I do not wish to relive or return to an earlier time, nor am I interested in glossing over the hardships endured by those that lived in Shawnee and continue to do so today. Like the author and activist bell hooks, I instead return “again and again” to the place where my family lived––and to these recordings––to critically engage with the town and its people, to learn from them and move into the future. As I do so, these sonic fragments are carried along and begin to form a collage of sound, text, image, and living interaction: an archive of ideas and contexts that are connected to family and place yet do not stay put. Instead, they are continually changing, emerging, and dispersing.

- Brian Harnetty, 2015